When I was in New Zealand last year, I was asked by locals what social benefits are given to Native Indians in the United States. I was tongue-tied partly because I was ignorant about the subject, and partly because my Kiwi host talked enthusiastically and with great pride about the Māori and their importance in the fabric of society. I knew no way that I could brag about the indigenous people of my country receiving treatment equal to that of the Māori. In fact, after I came home I turned to Google search for everything about Native Indians. Each headline read grimmer than the previous. Are the Indians living in a destitute nation within a wealthy nation?

I made my new year resolution in the first post of this year. I dedicated 2020 to endangered species and languages. Unfortunately, the covid pandemic hit every corner of the globe in 2020. Reports about endangered species and languages are affected in the lens of covid. Each time I read about Native Americans, my heart sank. Here are a few titles from the media to ground you to 2020:

How The Pandemic Threatens Native Americans—and Their Language (The Economist, May 19)

Navajo Nation: The People Battling America’s Worst Coronavirus Outbreak (BBC, June 16)

The Navajo Nation Faced Water Shortages For Generations—And Then the Pandemic Hit (The Verge, July 6)

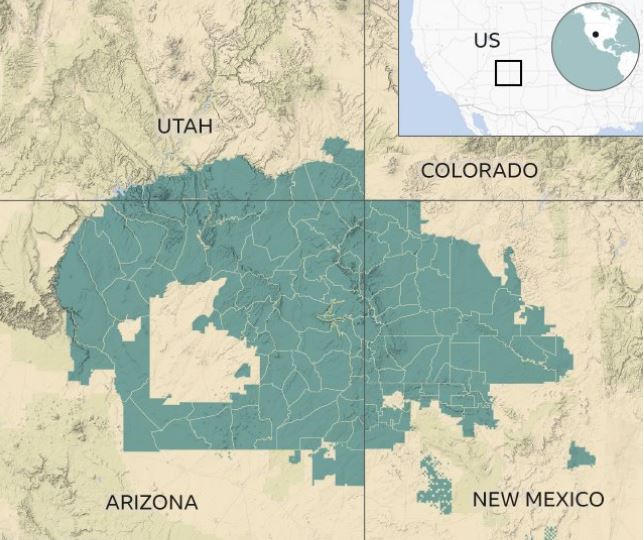

The water problem of the Navajo Nation is chronic but in the lens of covid, it becomes inhumanely acute. Arizona and New Mexico are an epicenter of the covid pandemic in the United States, and the Navajo Nation—the largest Indian reservation with more than 173,000 people—is right in the middle of it, suffering from water scarcity amidst a pandemic. It is hard to imagine how many people can escape from this dire situation. How can many smaller Indian tribes whose names don’t even register to majority Americans live in these troubling months.

I can’t tell my Kiwi host these frightening stories. I can’t even justify my own perception of the well-known statement in the United States Declaration of Independence that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Access to water and sanitation is recognized by the United Nations as human rights. In 2020, there are still American citizens on the soil of their native land who are deprived of these basic human rights. How preposterous!

Many homes in the Navajo Nations are multi-generational. Without the availability and access to water, thousands of indigenous residents cannot wash their hands regularly, making it easier to spread the virus to elderly and vulnerable family members and neighbors. The nightmare in poor African countries that covid can devastate communities with weak public health systems can also take place in the world’s superpower and ironically labeled “Made in USA.” In Navajo, coronavirus is translated as Dikos Ntsaaígíí-19, or Big Cough-19. Given the fact that the elders who speak the tribal language fluently are among the vulnerable age group of Big Cough-19, how many of them will survive to explain the nuances of Dikos Ntsaaígíí-19 and Big Cough-19?

What struck me was the fact that the Navajo Nation sprawls across three states—Arizona, New Mexico and Utah with an area of over 27,000 square miles and has only 13 grocery stores. The size of the Navajo Nation is often compared to that of the state of West Virginia. Months ago I read an article that finding a Dollar General store in West Virginia was much easier than finding a grocery store. I wonder how many Dollar General stores are in the Navajo Nation.

We don’t see Dollar General stores in metropolises like Washington DC. But we do see grocery stores become an indicator of socioeconomic changes and well-being. Even in a city like DC, which is small compared to Houston, Texas, grocery stores are not evenly located in eight wards of our wealthy nation’s capital. In 2016, there were 49 grocery stores in DC and the average number per ward was six. A social group found that Ward 7 had two full-service grocery stores and Ward 8 had just one. Whereas the highest count was in Ward 6 with 10 full-service markets and three more on the way.

We don’t see a fair number of grocery stores in West Virginia and in the Navajo Nations. Should we adopt Dollar General stores as a new socioeconomic indicator for rural America? A typical way for leaders who have the ostrich mentality is to look for comparison to confirm the self-belief that they are not in the worst scenario. Following that mindset, should West Virginians see themselves better off by comparison to their fellow citizens in the Navajo Nation? But water contamination has plagued West Virginia for years. A notable case was DuPont’s water contamination with chemical C8, which was even made into a 2019 movie Dark Waters starring Mark Ruffalo. Another was the 2014 Elk River chemical spill. A 2019 study found that West Virginia counties are among the “worst in the nation” for drinking water violations. Water scarcity and poor water quality. Is this a choice for destitute citizens in a developed country in 2020? Is this the contemporary rendition of A Tale of Two Cities?

While we think of the people from a destitute nation within a wealthy nation, a nation of polarized opinions and agendas, let’s also ponder the classic quote from Charles Dickens that can be applied to the fight against the pandemic:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”