Reduce, reuse, and recycle. This familiar phrase has been around since the American environmental movement spread rapidly in the 1970s. Minimize the amount of waste we create, use items more than once, and put a product to a new use instead of throwing it away. How many of us have done all three? If we look at today’s scrap statistics, we may be dismayed that the progress of this minimalist lifestyle is pathetically slow. According to the EPA, a US federal agency, out of 267.8 million tons of municipal solid waste (MSW), or trash, that was generated in 2017 in the country, 35.2% was recycled, 12.7% was combusted for energy recovery, and 52.1%, that is, more than 139 million tons of trash, was landfilled. In Junkyard Planet by Adam Minter, the author dubbed the US “the Saudi Arabia of Scrap” for the reason that there’s more scrap than the people can handle on their own. The US is a land that lacks real demand for manufacturing materials on this junkyard planet.

It was then, it was now. The US has not changed much in terms of speeding up e-waste recycling. E-waste represents only a small percentage of the overall MSW, and yet it has harmful effects. In fact, since China banned foreign trash imports in 2017, the US’s e-waste is now found at the border of China, precisely, Hong Kong. Together with the electronic discards generated locally, Hong Kong has become a major global hub for dismantling electronic waste, legally and illegally. What Adam Minter, a Bloomberg News journalist, observed in China ten years ago during his research for his first book, Junkyard Planet, is as familiar as old jeans to me. I grew up in Guangzhou, the capital city of China’s economic powerhouse Guangdong province. As Minter wrote, “interests matter more than values” in an often-overlooked scrap industry. What is perceived environmental in e-waste recycling is more or less about how much money the scrap could be regenerate if it is reused. In my mind, recycling is to reuse.

Electronic goods contain a plethora of toxic components, including mercury, lead, cadmium and lithium. If not handled properly, e-waste would cause a series of environmental hazards and public health problems. The so-called recycling in developing world is when unwanted electronics are resold to locals who cannot afford firsthand goods. If these electronic discards cannot be repaired and resold, they will be detached—the plastics and metals will be separated and resold to manufacturers to produce new products. The remainder of the scrap which cannot be reused will be combusted for energy recovery or landfilled. In developing countries, many low-income families are dependent on recycling scrap for a living. In China, many migrant workers from impoverished communities come to big cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou to make their first bucket of gold from the scrap trade.

In his book, Minter showcased his expertise in the industry after he spent years learning the trade as a son of a Midwestern American scrapyard owner. He compared recycling practices in China and the US, and traveled to world’s overlooked corners to research scrap recycling. He wrote, “I’ve seen dumps like Leonard’s in India, Brazil, China, and Jordan, salted with impoverished people, often mothers and children, literally scraping at a living. The most famous is surely in Mumbai, movingly depicted in the film Slumdog Millionaire, its orphans grubbing in search of just enough recyclable trash to exchange for food.”

To international e-waste watchdogs, Guiyu in Guangdong province is like an old friend. It used to be one of the world’s most dangerously polluted towns by e-waste. Its name often appeared in Western mainstream media critical of China. In Junkyard Planet, the author also did an exposé about his adventure on site. Today, despite that the legacy of e-waste pollution remains visible, the government-led makeover is taking effect. Noticeably, the outdoor scrap business has moved indoors, and a wastewater treatment plant has been installed (See below video). The town has been transformed into China’s experiment with circular economy. The EJ Atlas, an environmental website, has this description about Guiyu National Circular Economy Industrial Park. It wrote: “Guiyu is a lesson that a ‘war on pollution’ is best fought through preventing the pollution in the first place.”

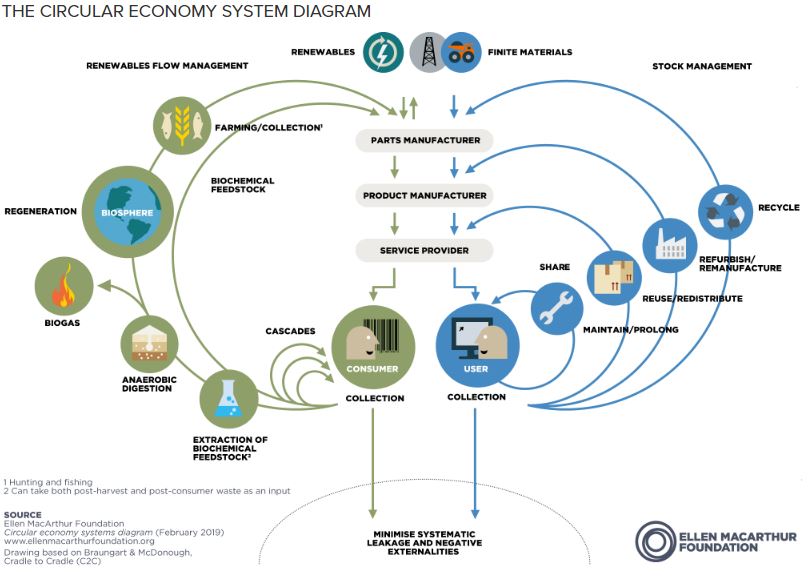

When it comes to e-waste pollution, what happened in Guiyu is repeated elsewhere in inland provinces in China as well as by desperate people in Ghana, Nigeria, India, Bangladesh, and places that you may not think of. To Americans, recycling e-waste is a moral issue. It’s a feeling-good internal call for such action to take place. There is no law enforcement or penalty to individuals if we choose to dump our personal devices into garbage. There is also no incentive for consumers and sellers to slow down the pace of replacing their older but functioning devices. In the book, Junkyard Planet, the author even explained plainly that Apple boasted its efforts to “use fewer and greener materials” and yet “all the while making its devices more difficult for individuals to repair and refurbish.” Take the MacBook Air for example. The author expounded that “. . . [its] thin profile means that its components—memory chips, solid state drive, and processor—are packed so tightly in the case that there’s no room for upgrades (a point driven home by the unusual screws used to hold the case together, thus making home repair even more difficult).” Indeed, refurbish and repair are two of the five “Rs” of circular economy. The other three “Rs” are “reduce, reuse and recycle.” As a new iPhone model—the 12th generation of its kind—is the talk of the town this fall, shouldn’t Tim Cook rethink how to attract loyal Apple fans with circular economy in mind?

In my years living in China, I witnessed and even participated in the scrap recycling trade as an environmental (and perhaps a little mercenary, too) resident of Guangzhou. I saw how hard-working laborers painstakingly sorted cardboard and tin cans in piles and how dexterously they detached metal parts from old TV sets and refrigerators. If I frequented the recyclers in walking distance from my high-rise apartment building, the owner recognized me and they usually offered me better prices for my scrap, which in their eyes were treasure.

Unlike in China, I can’t sell my used newspaper and home appliances to an American recycler. The best I can do is to get a tax deduction slip after I donate my used goods to nonprofit charitable organizations. No money transaction. I only can leave shipping boxes in the recycle bin or have the mover haul away the old appliance when he installs the new. I may end up giving him a tip rather than he giving me the monetary value of my old junk. Welcome to the gratuity-friendly American labor market! As Minter wrote, “Recycling is what happens after the recycling bin leaves your curb. Home recycling—what you most likely do—is just the first step.” I often wonder: How much will the recycler gain from my recycling bin?

Compared to China or other OECD countries, the US is not doing enough in e-waste management. Whether it is a matter of law enforcement or a change in consumer behavior, the US remains in its own bubble of exceptionalism and extravagance. As China is tightening rules on hazardous waste disposal, upending the global recycling industry, will the US stay inactive? Is recycling “a morally complicated act” in our shared junkyard planet?