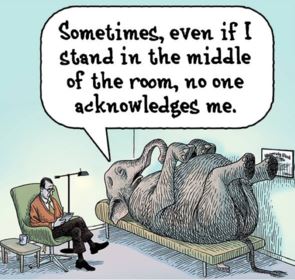

There are two more months left before we leave 2020 behind. Like many of us, we have so much undone, so much to grieve over, and so much to hope for a change. Since early February, there has been a popular opinion among the intellectuals to compare climate change with covid in terms of its scale and scope of damage and destruction to humanity. Both climate change and covid are the elephants in the room in 2020 and beyond. Yes, two elephants!

The pandemic has ruined our plans—travel, international cooperation, the summer Olympics, religious assembly, concerts, graduation, wedding, honeymoon, and even funerals, we have to scratch them off or prepare them with safety measures in a lens of covid. We know what the problem is and what a nuisance the problem is, and yet we run out of resources to tackle it. Nor do our leaders see eye to eye with the suffering, silent majority. This covid elephant is trampling our lives. How preposterous it is that liberal countries cannot rein the beast while authoritarian states are manipulating data about the beast! What’s worse, the United States has let it loose in the room. We’ll be with the elephant (and its relatives, too) for a good part of next year, too. Welcome to the elephant room.

In light of two more months left in my year of advocacy for endangered species and languages, I’m supposed to share with you my comparative study of e-waste recycling between the U.S. and China. But I’m having an embargo of releasing my yet-to-be-published essay as I’m still awaiting a response from the Economist. I doubt the newspaper will pay attention to this small potato. After all, the newspaper is one of the few wise elephants in journalism. I’ll give a couple more weeks for my message-in-a-bottle application to float ashore as my hope dwindles.

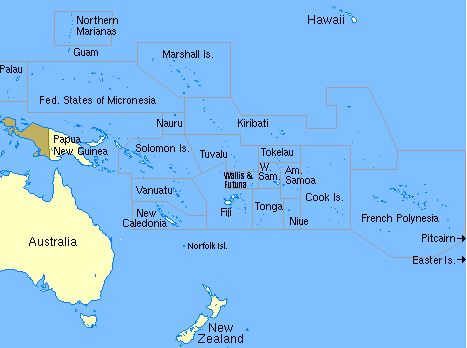

Here is the plan. (Sound familiar with this mantra?) I am going to focus on my virtual tour of Kiribati this month. And I will conclude my 2020 year of magical thinking about e-waste recycling, linguistics and other topics in December. I’m not sure where I will be in 2021, and what sort of destiny for this column lies. I do know that if I survive 2020, I’ll have had the longest confinement within 15-miles radius from my home. My fruit for thoughts and for tummy is declining and my reverie grows stronger in my pent-up frustrations. Fiction is my vaccine now. One of my villain character studies is the 45th President of the United States. (Have I told you my first caricature attempt taught by KAL, a renowned cartoonist from the Economist, that brought me long-awaited laughs is my villain object of study?) Virginia Woolf once said, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” I have only one—the room.

This October I’m thrilled to learn that an international treaty banning nuclear weapons has been ratified after the United Nations gathered 50 signatories from member states. Together with, Nigeria, Tuvalu, South Africa, Vietnam, New Zealand, the Vatican among others, Honduras became the 50th country to ratify. None of the five permanent members (all nuclear weapon holders)—China, France, Russia, the U.K. and the U.S.—have ratified the nuclear weapon ban. If my villain object of study has unified tens of millions of early voters domestically, he certainly has reinforced the opposition sentiments of these five elephants in the UN to a peacemaking nuclear weapon ban.

This is only the beginning of an end of 2020.

Kiribati (pronounced Ki-ri-bahss), a former British protectorate in the equatorial Pacific, won independence in 1979 and joined the UN in 1999. Since then, the island state composed of 33 coral atolls, with the distance from the easternmost to the westernmost island equal that between New York and Los Angeles, has been an active participant in international efforts to combat climate change.

Geologically, Kiribati is a low-lying country of which many atolls are rising just 6.6 feet—as tall as Michael Jordan—above sea level. The highest point is Banaba, a controversial island, which reaches 285 feet—as high as a thirty-story building, give or take—above sea level. Unfortunately, Banaba is now sparsely inhabited as a result of overexploitation of its rich phosphate by British colonists and locals. The phosphate mining (for fertilizer) had been a major revenue for the island nation and yet the environmental damage has forced out Banabans to resettle in northern Fiji. So historically, the I-Kiribati, a name that Kiribati’s indigenous residents give themselves, have been victims of environmentally-induced migration and displacement. Socially, except for the few outliers such as former president of Kiribati Anote Tong who is dubbed “climate warrior,” I-Kiribati by and large identify themselves by clans and families and religion. They look for Noah’s Ark more than praising President Tong’s climate leadership. Doesn’t it draw a parallel to the climate deniers in the coal country United States?

Kiribati is a perfect place for us to learn and relearn the trees of life against the backdrop of the climate elephant in the room. And in 2020, joining with the covid elephant, we have two elephants in the room. Welcome aboard! Stay tuned for the next post.