Speaking of Africa, I associate it with American travel writer Paul Theroux. His writing about Africa is one of my early exposures to this lesser-known continent. If reading Paul Theroux’s work arouses my curiosity, reading Howard French’s China’s Second Continent hits home.

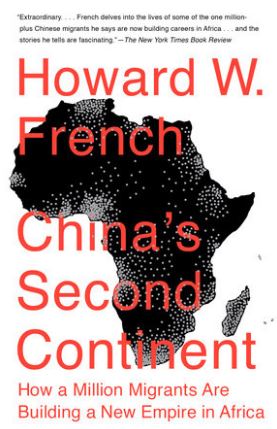

The full title of the book is China’s Second Continent—How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa. This is not a new book. It was published in 2014 and was French’s 3rd book. I picked up the book as part of my research for my own book project. This was how I got to know French’s remarkable journalistic repertoire about Africa and China.

As the author wrote, “With two billion Africans, including vastly more people who will have attained middle-class status or better, and over a billion Chinese, whose lives will be much more affluent, much more globalized and deeply involved in every corner of the world, it was possible to imagine the unfolding relationship between China and Africa as one of the most important in the world.”

Former President Barack Obama once said the US-China relationship is the most important bilateral relationship in the 21st century. If that’s the case, the development of Africa, directly or indirectly, matters for US’s economic growth as well. China is the biggest exporter to the US. And yet, China is hungry for Earth’s finite resources for its supply chains. China is providing goods to its own domestic market with the world’s largest population and to the US and other countries. No way can China meet this gigantic demand without absorbing raw materials from elsewhere.

When the Europeans colonized African countries four hundred years ago, they were doing the same to extract local resources for their own economic growth. Four hundred years later, Chinese opportunists craved the natural resources on African soil—from metals and timber to arable land and fishery—as much as the European colonists in yesteryear. The European colonists gave no damn about the economic and environmental growth of their colonies, neither about the wellbeing of the African people. Instead, they exploited both natural and social capital. The study of the transatlantic slave trade led by Glasgow University will shed more light on the human exploitation during colonialism.

Several times the author writes that the Chinese disagree that their presence in Africa is synonymous with colonialism. In their eyes, the Chinese provide opportunities for them and the Africans by taking on infrastructure projects. It’s a win-win deal as the Chinese believe in French’s book.

There is no slave trade in China’s economic exploration of Africa. But according to French’s accounts, fewer local workers are hired by the Chinese infrastructure projects; and they receive much lower pay than the Chinese workers. While the Chinese workers get better work safety protection on a metallurgy site, their African counterparts wear near nothing or shoddy materials for protection.

This condition reminds me of an award-winning documentary film, American Factory. In the film, the Chinese workers get the job done fast and in great quantity, and yet, the employer neglects the workers’ safety and well-being. The employer dismisses American workers who form a labor union and fight for labor rights. The operation in Africa is no different, and even worse. I sympathize with those angry African workers and activists.

(To be continued click here)