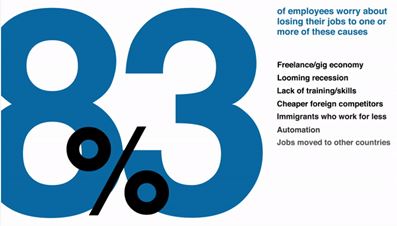

What are the basic needs of a person to survive? How many days can a person survive without food? How many days can a person survive without water? During my covid months, I constantly associate these questions with my sustainability case studies of South Africa, Laos, the Sundarbans in India and Bangladesh, e-waste trade, and now, Kiribati. My conclusion is for the low-rung population around the world, people strive for food, water and shelter every single day, presumably they’re all clothed and civilized. Economic migration is closely tied to our basic needs. Aren’t we who live in developed countries also making our days count to meet our basic needs in covid-afflicted 2020?

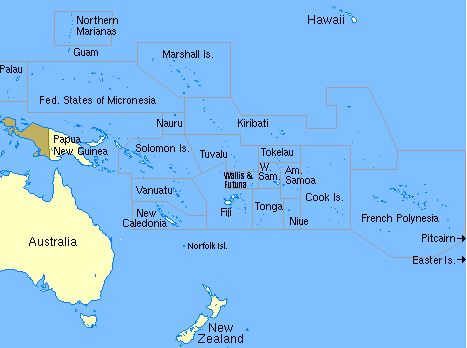

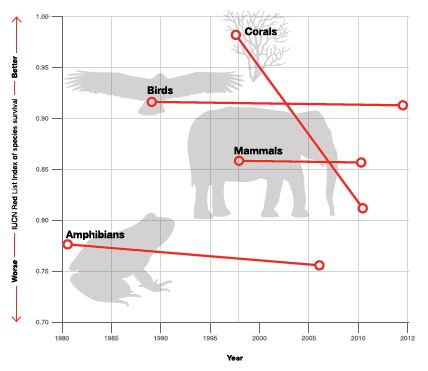

With global warming in sight, Kiribati is among the world’s first countries that will disappear under the sea in this century. The country that falls into all four hemispheres—northern, southern, eastern, and western—is also a destination for mankind to witness the fragility of life without water, food, shelter, and telecommunication. According to the World Bank, despite the rising number of telephone connections, Kiribati is one of the least “connected” countries in the world. Out of the 33 coral atolls, only 21 islands are inhabited. And yet, the majority of the population either has no access to information communication technologies (ICT) or unable to afford the service, which is often unreliable. Wouldn’t isolated Kiribati be an ideal place where a message in a bottle could be washed ashore?

Connectivity enables us to understand the world and communicate with our own species. Without the Internet, I doubt big countries can function with pride and prejudice in 2020. In Small Island Developing States like Kiribati, unless you’re holding high office like former President Anote Tong, you won’t be able to travel around the world to campaign for global climate action and leadership. People in Kiribati are innate optimists and their worldview is not shaped by social media nor science. Their livelihoods are not dependent on the Internet of things (IoT). Their simple lifestyle boils down to the simple basic survival activities of eat, drink, poop, pray, sleep and trade. You may call this pattern “a short-term, self-rescue system.”

Humans are short-sighted animals. In the world of connectivity where people are fed with overloaded data, we become less patient and prudent. Instead, we are more judgmental and siloed. As the Bard quipped: “We suffer a lot the few things we lack and we enjoy too little the many things we have.” In the days of Benjamin Franklin where there were no telephones or the Internet, leaders made plans so far-reaching that immortals today can still see their legacies influencing our life. Colonial legislation is one example. Nevertheless, we have everything and we don’t seem to find a fungible solution that will sustain our life without worrying about food, water, safety, and in Kiribati’s case, land too. With good healthcare, people can now live as long as 100 years (it’s less fortunate for I-Kiribati whose average life expectancy is 68 years in 2018). Our sustainable development plans often set in 2050 and 2100. What will happen after 2050? 2100? Our lifetime won’t reach that far, but does that mean we are okay to leave our problems to future generations to solve? Are we solving our forebearers’ problems now?

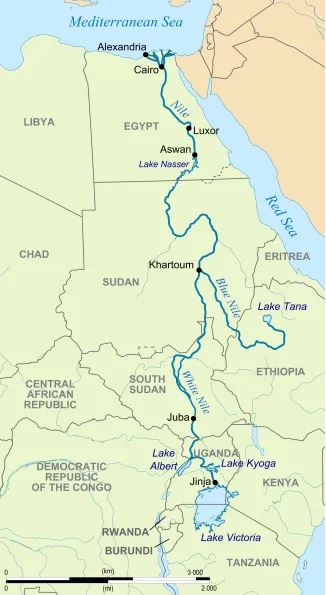

If we put aside climate change, what threatens I-Kiribati’s survival is truly water and sanitation. That explains why Scientific American crafted this alarming title in a 2015 article: “Kiribati’s Dilemma: Before We Drown We May Die of Thirst.” Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink. I found these three facts about my back-to-basics questions in the beginning of this piece: Humans need food and water to survive. At least 60 percent of the adult body is made of water. A human can go without food for about three weeks. It would typically only last three to four days without water.

Where can you get fresh water in Kiribati? Glaciers, lakes, reservoirs, ponds, rivers, streams and wetlands—these geological features are either non-existent or inaccessible in Kiribati. Groundwater is the main water source. However, overcrowding in South Tarawa has snowballed the pre-existing condition of water scarcity and poor sanitation, accelerating the vicious cycle of poverty, or in economics, a poverty trap. According to the World Bank, the population of South Tarawa grew from 3,013 in 1931 pre-independence to over 40,311 by 2005. The density in Betio (pronounced Beh-so), one of Tarawa’s neighborhoods, is comparable by an NPR reporter to Hong Kong whose high-rise housing is at exorbitant prices.

Access to safe water and basic sanitation are human rights. Water issues in Kiribati are acute with or without the lens of climate impact. Metals and chemicals from mining activities and agricultural chemicals have polluted Kiribati’s coastal waters. The lagoon of the South Tarawa atoll has been heavily polluted by solid waste disposal. No tourists and few residents would concern about New York City’s underground sewage system. Out of sight, out of mind. Such aged but functional urban sewage system in NYC is a dream in Kiribati. If you care about quality of life, diversity, and changing other people’s life, water issues are the first and foremost threats to survival in Kiribati. The lagoon in low tides reveals the true color of this remote island nation.

The poverty trap can be broken but it requires immediate action and long-term planning. Education and healthcare will provide foundation for any underprivileged global citizens to survive and even solve their epidemic problems. An old saying goes, you don’t give them fish, you teach them how to fish. Water is a lever. Like covid, diseases can wipe out a population too. Leprosy is one of the waterborne diseases that are caused by pathogenic micro-organisms that are transmitted in water. And Kiribati is one of the few countries in the world that still has leprosy.

Rising sea levels not only damage forests and agricultural areas but also contaminated fresh water supplies with salt water. Rising global temperatures increase drought periods. Just imagine, how to survive on a desert where there’s neither rainfall nor clean groundwater?

If Hong Kong were drowning due to rising sea levels like Kiribati, Hong Kongers could migrate to mainland China or elsewhere where democracy lies. Kiribati has no “motherland” to fall back on as it is drowning. The truth in 2020 is Kiribati is a sinking land with an increased population for limited fresh water reserves. Is this the basic brutality of Darwinian survival for the fittest? Stay tuned for the last post of the series about Kiribati’s climate adaptation.