China’s mainland population has reached 1.40005 billion at the end of 2019, with another overall gain of 4.67 million people, according to the National Bureau of Statistics on January 17 this year. (Sources: English / Chinese) I have to upgrade my numeral-retarded mind now. Remember, there are 1.4 BILLION people in China, excluding Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and oversea Chinese nationals.

Since I knew how to count in English in my teenage years, I have told English-speaking foreigners many times the population in China in order to stress the country’s bigness. From 1.1 billion to 1.2 billion to 1.3 billion over the last two decades, I have quoted the big figures in English in my verbal presentation as well as my writing. Yes, for instance, it was about 1.3 billion people when I wrote my memoir, Golden Orchid.

Billion was a big number to the younger me; even today a billion is still too large for me to fathom. I am used to quantifying billion in money terms thanks to China’s money-oriented mindset. Imagine that every Chinese citizen has one yuan (yuan is China’s currency), all the yuan put together, the total amount will reach to more than 1.4 billion yuan.

That is surely a big number. Because of its largest population in the world, China has a wealth of big data, resulting from the rapid development of telecommunication and personal services that are heavily reliant on smart phones. From applying for travel visas to Hong Kong and Macau to hailing a cab in a city and grocery shopping, Chinese people can get all done at their fingertips. If you walk around any cities in China, you will see the same picture: people of all ages looking at their phones. This is really a great leap forward from yesterday’s bicycle kingdom in which about one billion Chinese nationals were riding bikes on streets of all sizes.

Because of the data boom, occupations that I did not heard of twenty years ago mushroom today in all sectors. Workers don’t just work in manufacturing factories where computerized machines churn; they also work in data labeling facilities with desktop computers. Jobs abound in logistic and shipping companies to deliver packages and take-out food, and in media firms to copywrite contents for applications on electronic devices. Workers at data factories are on the 9-9-6 working hour schedule—work from 9am to 9pm, 6 days per week—to turn raw data into fuel for machine learning, which is a key component of China’s AI ambitions.

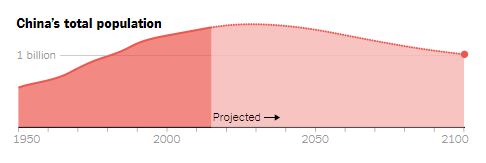

China doesn’t need public criticism of the country’s family planning policies. The numbers in the national statistics speak for themselves. The country’s working age population—between 16 and 59 years old—has declined by 890,000 from 2018 to 896.4 million last year. 2019 marks the third consecutive year when overall number of births dropped. Divorce rates are hitting records. In the first three quarters of 2019, about 3.1 million couples filed for divorce, compared with 7.1 million couples getting married. Chinese government scholars estimate the country’s population will reach a peak of 1.442 billion in 2029.

China needs talent for technology progress. That is human capital in the economics term. Apparently, the working age population is shrinking gradually. And more and more Chinese young couples are moving to cities where everything is expensive from food and health care to housing and education. Having one child is too much for many urban couples. Perhaps China will have to develop some sort of AI technology that can fill the possible deficiency of human capital.

Judging from almost thirty years’ of a One-Child Policy and the current slow birth rate, China will achieve the goal of eliminating extreme poverty by the end of 2020. China’s poverty-stricken areas are located in landlocked provinces and remote villages inhabited by ethnic minorities. So far, the government has established more than one hundred thousand industrial bases covering almost 92% of poor households in the country’s impoverished regions. China’s goal of fighting against extreme poverty is not insurmountable.

As for the long-term future, unless China abolishes the hukou—household registration—system and welcomes foreign workers, the world’s most populous country today may soon lose its top place to India.