For weeks, I’ve been carrying the burden of this question: Are we really living in an age of dematerialization or in the opposite?

Based on the idea championed by MIT scientist Andrew McAfee, a smartphone combines all the functions of a recorder, a radio, a CD player, a camera, a dumb phone, a compass, maps, a phone book, a television and many other products that we may only can see in the museums today. Zillions of applications for electronic devices will make our life easier and simpler. We can do more efficiently with fewer tools and steps. This is dematerialization coined by Mr. McAfee. If you read his book More From Less or watch his YouTube Ted Talk about dematerialization, you’ll be acquainted with McAfee’s positivity in the future of the Anthropocene.

I question whether McAfee overlooks the laborious process of manufacturing smartphones—or, as a matter of fact, the making of many other “smart” devices—and the multitude of abandoned electronics exported from the wealthy countries to the developing countries. Yes, I am talking about the e-waste industry.

When Verizon Wireless and other competitive carriers regularly remind the customers that it’s time to renew their smartphones by the end of contracts or during a promotional period, American mobile phone users are given incentives to renew their phones to the latest model. Apple Inc. and Samsung also dole out all sorts of promotions to encourage loyal customers to switch and replace their cannot-let-you-get-out-of-my-hand devices.

So it is in China. In addition to Apple and Samsung, Chinese customers face a dazzling market of Made-in-China smartphone brands. From Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, Xiaomi to the lesser-known Tecno, Zte, Meizu, and Coolpad, they fit different household income earners. Lenovo is like Microsoft, jumping from the PC world to the smartphone world. Microsoft has acquired the Finnish firm Nokia to develop its mobile phone Lumia products. You can see Lumia phones in China, too.

Our obsession with buying the latest screen devices of all sizes is contributing to mounting piles of electronic waste. When my journalist colleagues covered the labor rights issues at sweatshops-like the Foxconn factories in China (Foxconn is Apple’s biggest original design manufacturer), I had the opportunity to learn what makes a phone smart.

From AMOLED displays to lithium-ion batteries and to the most complicated SoC—short for “System-on-a-chip”—which I called “the brain of a smartphone,” not to mention the cameras, the sensors etc., every component of a smartphone involves chemical and physical reactions of natural resources. Metals such as aluminum, copper, lead, zinc and others are vital resources for components used in smartphones and gadgets. Heavy metals could contaminate the work site and the entire community. Many Southeastern Asian countries as well as China are extracting, or even exploiting, local resources—both from nature and from workers in sweatshops—in order to assemble a “dematerialized,” multi-function device. While Apple Inc. reaches its goal of making big profits for selling more products at a low cost of labor and materials, the company is doing all it can on damage control of its poisoning supply chain abroad. You won’t find much on Google about this, sadly.

Electronic waste is extremely toxic. The components of every piece of electronic devices contain toxic chemicals in order to enable the chemistry and physics in the device to kick efficiently as well as to draw your eyeballs to that attractive appearance and packaging.

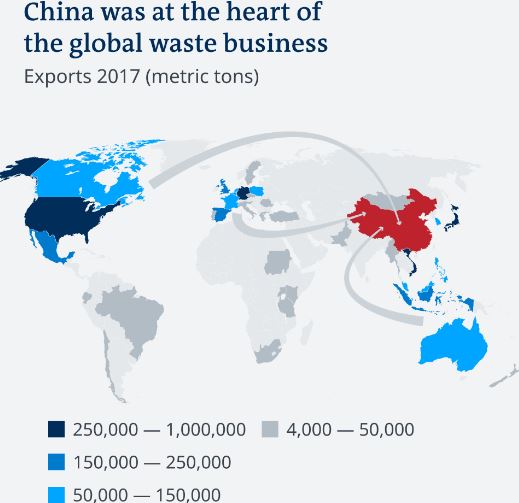

For a long time, the rich world has dumped abroad what its people don’t want. Indeed, the attitude of NIMBYs—Not In My Back Yard—has been an unwritten consensus among the developed countries. China is one of the favorite destinations for global waste—yes, the Chinese call it “yáng lā jī,” the foreign trash. China wanted it. China needed it. As laborious it was to assemble a smartphone, so it was laborious to dismantle the scraps to make them useful again. For their livelihood, tens of millions of low-rung Chinese laborers, as well as those in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ghana, Nigeria and many other countries, would sit together in their poverty-stricken villages to sort out bundles of plastics, wires, cables and other garbage. They would work at the scrap yards exposed to hazardous chemicals on a regular basis just to make both ends meet.

A record shows forty percent of the US e-waste has been dumped illegally in Hong Kong. In the name of “green laundering,” which is synonymous with money laundering, electronic waste traveled illegally from US recycling companies to Taiwan, Hong Kong and other developing regions and states.

How can we dematerialize if we create excessive waste from a small-sized product? Does a merchandiser really have little obligation to control the impact of an externality—pollution? (Read on. I will explain what an externality is.) Can a government really keep eyes shut to the e-waste pollution domestically and globally?

An externality is an economic term, meaning the cost or benefit that affects a third party who did not choose to incur that cost or benefit. By introducing this term, I hope I can bridge my argument with an economist’s mindset to help us understand why the merchandiser and the consumer—the polluters on the production side and on the consumption side of electronic devices—can, and should, take action to turn negative externality into a positive one. If we still believe the power of “We the People,” consumers, conscientious merchandisers and responsive governments can turn a “double negative” externality into a positive one. Solving the issue of e-waste is a sustainable, positive externality.

It is estimated that after the introduction of the first iPhone in 2007, more than seven billion smartphones have been produced in the following decade. And many of them have already ended up in the dump. The world population is more than seven billion people. But not all these seven billion people are smartphone users. The number of smartphone users worldwide in 2019 surpassed three billion. China, India, and the United States are the countries with the highest number of smartphone users, and also the biggest e-waste producers.

We use less, but we poop a lot.

China has started to understand the waste problem. Beijing announced in 2017 that China would be reduced its import of global plastic and paper waste. Until then, China had been taking in up to 56 percent of the world’s plastic garbage to recycle, 60 percent of paper waste from the U.S. and more than 70 percent of paper waste from Europe, according to the German state media Deutsche Welle. As a result, the non-profit US-based group, Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, sees from the first quarter of 2017 to October 2019, US exports of plastic waste to China have plummeted by 89%.

I always say it’s a fate that my so-to-speak “formative years” of understanding modern China and modern United States took place in Guangzhou and Pittsburgh. China’s strategic plan of “Made in China 2025” is happening now. Just like Pittsburgh’s yesterday which produced one third of the US steel in early 1900s and became the center of the “Arsenal of Democracy” in WWII, China is moving at its own pace away from the “world’s factory” which produces shoddy goods at lower labor costs toward a more technology-intensive powerhouse. Today, Pittsburgh has transformed itself into a university town of computer technology, research and medicine. China tightens imports of foreign trash just like Pittsburgh treated its air, rivers and streams polluted by the steel and coal industry. Guangdong is pioneering in treating its water and air pollution caused by industrialization.

So you see why I am skeptical about dematerialization if we don’t follow Steve Jobs to do some damage control. We don’t hold back the scientific truth; we hold back our e-poop.

As I’ve relieved my burden of the question of dematerialization. I am leaving more questions. Watch the space.

Will China’s e-commerce boom turn China’s e-waste into treasure?

Will China’s manufacturing powerhouse of Guangdong become the next global factory for higher-value products and services, such as AI technology?

Can the Big Four tech companies—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft—find solutions way ahead of their competitors in the e-waste industry?

And I have a proposal for you as a consumer:

If you can keep your smart devices a little bit longer, you are doing tremendous good to the planet and to future generations.

For those who believe in God and often pray for Him to “lead us from temptation,” control your temptation by holding onto your devices a bit longer.

When you renew your phones, laptops, TVs and many others, ask NOT what they can do for you, ask what you CAN do to your wallets and the landfills.

Saving the planet starts from your wallet.

Does this sound like a feasible proposal for you?

By the way, I’m not an Apple hater. In fact, I’m an Apple fan. Thanks to my graduate study about sustainability at Virginia Tech, I have a second iPad. I did my personal inventory. Under my ownership, I have three iPhones and two iPads. That is five Apple products per capita. For this good sales record, Steve Jobs is toasting in heaven now. Let’s make the Planet great again.

You can read my iPad Rhapsody here.