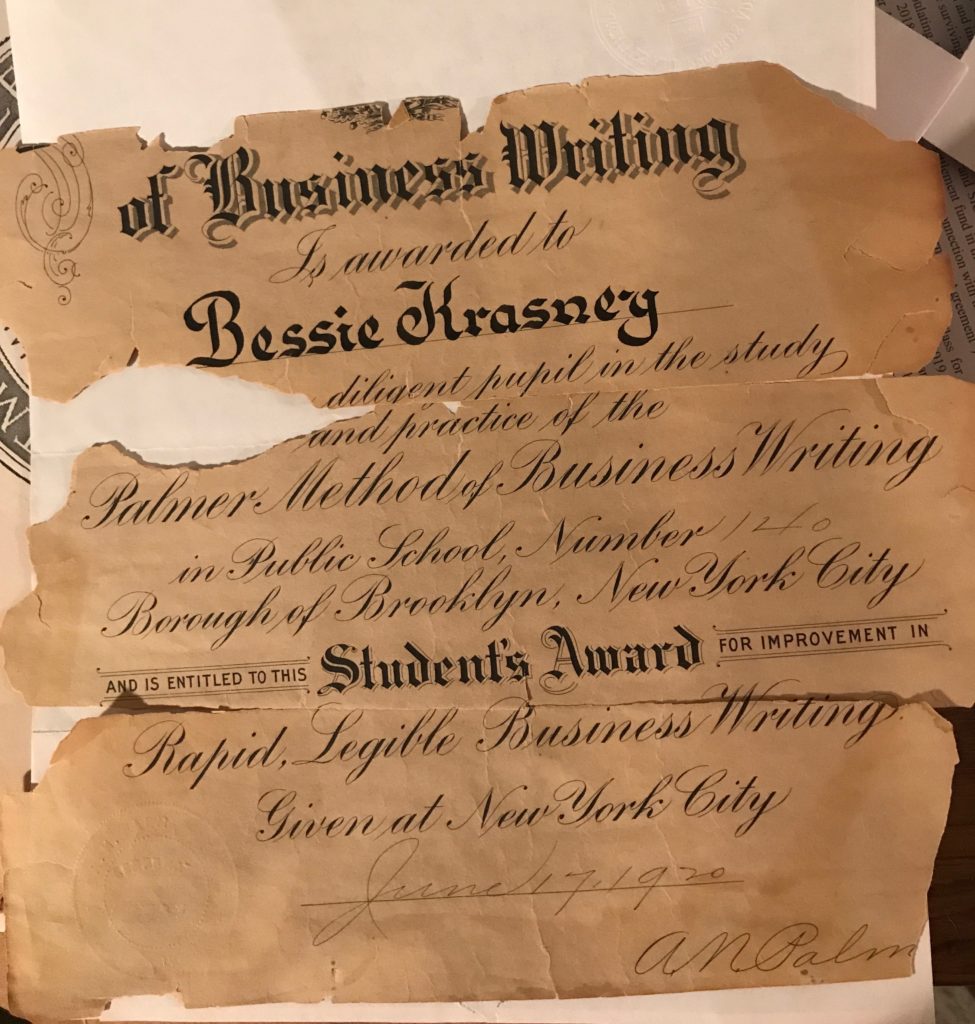

My American family recently discovered an old certificate dated back to 1920. It was an award certificate granted by a Brooklyn public school to the preteen Bessie, my never-met mother-in-law. The finding is not much a surprise to the family by blood. After all, other family members also keep some decades old files and photographs. But I was astonished when I held the yellow, crumbling broken pieces in my hand. I took the initiative to preserve them in one piece. Yes, just like a meticulous archivist. And I’m so proud of my little contribution to the family.

In my Chinese upbringing, I saw old furniture and old wares that my grandparents used in their lifetime. In my memoir Golden Orchid, I mentioned that black wooden desk which was my paternal grandfather’s effect. My late father said it was the family treasure in their impoverished life. I wish I could keep that desk but I had to give it up eventually in my recent sale of my late father’s apartment. Keeping family artifacts takes time and space. Most of all, the collector must have a loving heart of preservation. In big cities like Guangzhou, people now live in apartments. It seems hard to store old artifacts at home. I’m probably the most nostalgic in my family and yet, I live the farthest. My Chinese family is not as nostalgic as many American families with which I am acquainted, including the one I married into. Perhaps antiques remind my Chinese family of the loss of the owner. Perhaps in China it’s so easy to replace old goods with the new. Whatever reason, Chinese people are not zealous to collect family antiques unless they have market value.

I remember my late father used to tell me that during the Cultural Revolution, my paternal family had to burn the family registry to protect the family members from denouncement. Had we kept the family registry, I would be able to learn the genealogy about which the Japanese and the Americans fancy. In responding to the Communist Party’s campaign in the 1960s to destroy the Four Olds—Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas, countless historical evidence from the national level to personal use have been significantly destroyed and erased. It is a tragedy for Chinese future generations and even for the whole Chinese nation. Without the precious artifacts and records, historians cannot reconstruct fact-based historical accounts; our children and grandchildren will never know what happened in the past. Personally, I will never know my family stories. I am dying to know my family tree preceding my grandparents’ generation and even my grandparents’ untold stories.

When China condemns Japan for revising wartime history, I can’t help thinking—for centuries, didn’t Chinese rulers also dictate their own accounts of how history should be written? Burning books, destroying records, even killing the whistleblowers, these are the familiar plots used by ancient Chinese royals, and later were adopted in TV dramas. Now even such historical palace dramas that reflect power struggles are banned in mainland China. Because the authorities are in fear of “bad influence,” well, we all know the decision is more political than spiritual.

I may have gone off on a tangent. I just get sentimental when I see old stuff dated to the antebellum period in the US are still available in today’s yard sales and antique markets. Seeing collectors are telling stories vividly of the artifacts to their buyers, and now my American family members are actively talking about the history of that centennial old piece of family artifact, I lament the loss of my family history. As a matter of fact, tens of thousands of working class families like mine in China are told to believe what happened in the history from the perspective of the authoritarian government.

My standing ovation for Winston Churchill’s wisdom. He once said: “history is written by the victors.”

I’m with you, Prime Minister.