Whether you’re a climate change believer or a climate denier, global warming is happening. As the world is slowly returning to business as usual at the same time it is battling the first, second or third wave of the novel coronavirus outbreak, the Earth’s fever only gets stronger like the tropical cyclones hitting our shorelines. Humanity is heading for an irreversible future.

Unlike the covid pandemic that a forthcoming vaccine may curb, and antiviral drugs may pronounce the viruses dead, the destruction of a climate crisis cannot be undone. The native vegetation in the Amazon and the endangered species won’t come back to life after they die by human-induced forces.

The loss of agricultural crops in East Africa and India in the locust invasion this year sounds an alarm that there will be a spike in the loss of lives due to hunger and poverty. As warmer days are prolonging, the loss of seasonal changes in subtropical regions will cause a domino effect in our food chain—half of all life is moving as climate conditions shift. Climate refugees are on increase, and in the Arctic the male polar bear chases and eats the cub.

The warmer the weather gets, the more demand of electricity soars as people turn up their air-conditioning. If we still rely on fossil fuels as our energy sources, yes, business-as-usual, the oil and gas producers are happy for the market demand. But the Earth’s fever will reach its breaking point—the point of no return. Sadly, it’s not as melodramatic as a song with the same title in the musical The Phantom of the Opera.

Population grows regardless of the pandemic. As we return to business as usual during COVID-19, economic productivity continues and more people can afford basic needs including paying utility bills. The electricity demand soars, so does the emissions of CFC, the compound, chlorofluorocarbon, which contains carbon, chlorine and fluorine. CFCs are also known as freon that used for refrigeration.

Back in the 1980s through the early 1990s, CFC emissions had threatened ozone depletion. Climate skeptics until today still believe the Earth has fixed the ozone problem itself. Back then, the responsiveness in global governance made intergovernmental corporation possible. Bound by the Montreal Protocol, signatory countries gradually phased out the production and consumption of ozone depleting substances (ODS) including CFCs and HCFCs.

However, today is a drastically different world. It is a norm that countries run by populism and pseudo-populism like Trumpism will cut off global cooperation and politicalize basic science education. The US is now withdrawing from the World Health Organization; the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will take effect soon. The type of article that ran in 1992 about good and bad ozone is a rare fossil in today’s journalism. There is a knowledge gap about climate change and its impact, from governments to businesses, from lawyers to public school teachers. Science knowledge is fundamentally polarized among religious and political groups.

The pandemic has forced us to learn and adapt a different lifestyle. Yes, we lost tens of thousands of jobs created in the pre-pandemic business-as-usual. Nevertheless, during the pandemic, there are also hundreds of thousands of dollars being invested in online services led by Amazon, development of goods delivery by drones and robots, streaming entertainment services led by Netflix, grocery delivery and pick-up services such as Instacart and WalMart, communications tech firms such as Zoom Inc. and Facebook Messenger Rooms. And even bike sales have soared 300% in some major cities.

During the pandemic, vaccine trials are on the fast track by cutting corners. Scientific publishing is also fast forwarding and become accessible through preprint servers. Working from home may be actually more money-saving for some office folks than the pre-pandemic life they led. They save time commuting to their offices and they don’t need to rent expensive housing just to be near their offices in downtown. To money-sensitive employers, they also find their saving by not paying overheads like utility and office supplies during the lockdown months. Office rentals may be less desirable if employees and employers both find convenience in working from home with part-time office appearance just for social activities.

Chinese people are more experienced in responding to COVID-19 after the SARS outbreak in 2002-03. China’s presumed economy may decline during the covid months, but China’s online economy was impacted little during the same time. Back in the SARS outbreak, Chinese people were restricted from travel and the market was like what we are experiencing now during the covid months. But the SARS was a turning point for China’s e-commerce, giving birth to Taobao (Alibaba’s customer-to-customer retail website), JD.com and many other online retail competitors.

Drawing from the lessons of the SARS outbreak, perhaps we’ll be more open-minded about our irreversible future. Economy won’t go away but the finite natural resources will. Despite the pandemic, people still consume water, energy, food and entertainment in their shelters—they eat, work, learn, virtually socialize, shop and sell; technology has made all these activities possible at home. Like climate change, the housing economics is transforming our lifestyles as well.

Even for the labor-intensive tasks like meat packing and online order packing and shipping, the spread of automation and AI will replace humans. The pandemic has sped up this trend. Workers who use their hands today will need vocational training to use their brains for the future. To save American jobs, we need to boost the brain power of the American labor force.

Education is the key. Education is the missing link in our broken system of economics and social wellbeing, from pre-school education to adult learning, from the C-Suite training to the assembly line tutorials.

And yet, the low-rung labor force is the very group that lacks proper K-12 education. Getting a college degree for many low-income families is like going to the moon. Many of them rely on church support and nonprofit scholarships to finish basic education that is needed. A 2019 Gallup survey found that 40% of US adults believe in creationism, namely that God created them in their present form as opposed to evolution. A pre-pandemic survey shows 84% of Americans saying vaccinating children is important, down from 94% in 2001.

And mass media is not helping with the enhancement of public knowledge.

For an ordinary Joe, I can’t politicize my search for toilet paper during the covid months. But I do see the more toilet paper is made from non-recyclable sources, more trees will be chopped down, more fossil fuels and water will be consumed during manufacturing. And during the pandemic, our essential workers at the sewage treatment plants are also dealing with the epidemic of wipes and masks that plagues sewers and storm drains. Drain clogs have become a more costly and time-consuming headache during the pandemic. Who will bear the cost to repair? The beleaguered local governments especially for those who fought in the battle of public health crisis? Or the residents? Watch out for your utility bills.

I don’t care who has the highest rating on social media about the most graphic moment. I do care if I follow the presidential instruction to drink bleach and take hydroxychloroquine, I will die sooner.

I do care that not only health professionals but jobless folks are on the brink of mental fallout. Suicidal thoughts permeate in our nation—self-destruction is awful; mass shootings are fatal for innocents too.

We need hope. We need solutions. We need relevant news coverage.

Under COVID-19, few media outlets cover the gains side of the employment opportunities. Nor does it educate the target audience about the impact of climate change.

Perhaps we can start with the mass media, or even with journalism education, which has been shaped by interests of business-as-usual economy, to get more climate stories published. These stories involve ethics, equity, justice, business, economics, diplomacy, military, bio-rights, arts and science.

If the New York Times put climate stories on its front page every single day, if NPR’s on-the-hour headline included at least one climate story, or if the primetime TV news moved the White House story and presidential tweets to a less inconspicuous slot in the lineup, and instead, give front-and-center coverage on a small town in the Mississippi Basin combating flood risks, or a farmer in California struggling with drought, or climate refugees in Florida dealing with their uninsured livelihoods. Perhaps this sort of coverage would allow ordinary folks to connect better with mainstream media better as a means to find knowledge to adapt to the irreversible future.

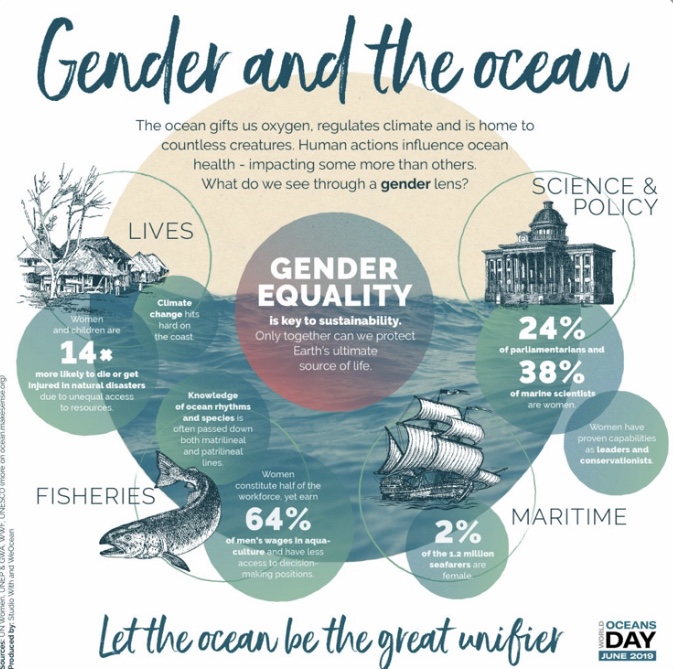

This year’s World Oceans Day falls on June 8. To most people, this UN holiday is no different from other official UN holidays like World Bee Day which was just past on May 20, or World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development on May 21. However, as climate change is happening and is gaining attention in the public, the World Meteorological Organization brings oceans on the agenda of the concurrent World Meteorological Congress. The theme of this year’s World Oceans Day is gender. According to a recent UNESCO report, women make up 38% in ocean science, 10% higher than in science overall. Gender-diverse and inclusive ocean science and marine meteorology are vital to create sustainable opportunities in the ocean space.

When we have a fever, we put ice on our forehead. When the Earth’s fever is relentless, we must find ways to cool the big body of water that composes the Earth.

I often like to talk about this analogy. On a rainy day I may complain about the bad weather, but the guy who sells umbrellas may have his best day. Here is another old analogy. A boy kicked a ball at the window of a barber’s shop. The window was broken. The barber had to spend the money he saved for an upgrade of his mirrors on the replacement of the glass. So the money didn’t go to the mirror seller but to the glass maker. In other words, the amount of money is the same, it depends on how the owner spends it.

Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” can’t be more timely in this irreversible present that leads to our future. He wrote:

“Two roads diverged in a wood / and I – I took the one less traveled by / And that has made all the difference.”

We’re heading for an irreversible future. However, if we can take the other path that is less traveled with the same amount of money, perhaps we will spend less on the damage and create more new opportunities that will actually bring more profits than we make from a world of business as usual. And that path is called sustainable development.