China’s “One Country, Two Systems” (OCTS) policy has been regarded as an experiment. It aims to integrate Hong Kong’s colonial system and way of life under British rule to the Chinese national picture after Hong Kong’s handover to China in 1997. This integration experiment is expected to be used as a model to demonstrate the possibility of reunification with Taiwan. China has promised that Hong Kong’s previous system and way of life would remain unchanged for 50 years. We haven’t reached 2047 but we’ve seen so many changes in the last decade in Hong Kong. Is the integration experiment over?

The latest top-down intervention is the reform of Hong Kong’s electoral system. It’s not surprising to see the overwhelming majority in China’s rubberstamp parliament favors one side in voting. Between yays and nays over any given bill the result can be as symbolic as one nay, one abstention and the rest of votes are yays. Will the scene be the same in a future Hong Kong Legislative Council (also known as Legco) in which all the lawmakers will be patriotic?

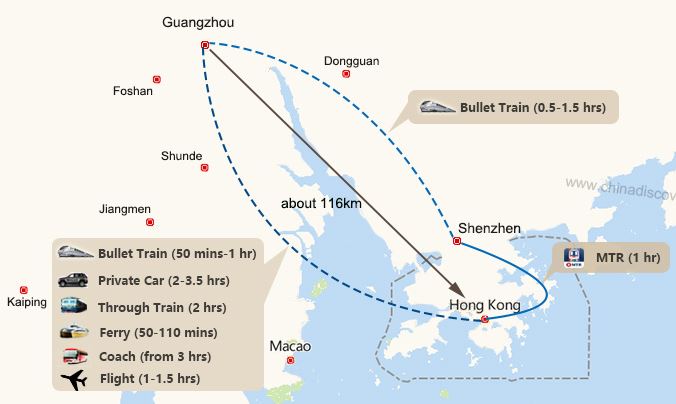

Because of my Chinese appearance and fluency in Cantonese, when I visit Hong Kong, Hong Kongers regard me as a hometowner. Likewise, I feel strongly with Hong Kongers about our shared mother tongue. Speaking Cantonese in Hong Kong enables me to understand deeper Hong Kongers’ pursuit of prosperity and democracy. Taxi drivers would become talkative when I spoke Cantonese to them. As did the owners of Dai Pai Dong, open-air food stalls and Cha Chaan Teng, Hong Kong-style cafes. They made me feel more at home even though I was only a visitor. When they learned I was heading for Guangzhou, they would still think my home base was Hong Kong, and I was only to “go up” to visit relatives. Guangzhou is located northwestern of Hong Kong. Thus, to Hong Kongers, “going up” in colloquial Cantonese means traveling northbound, as opposed to “coming down,” returning southbound to Hong Kong.

This is Hong Kongers’ true color—resilient and hard-working, polite and dignified. It’s heart-wrenching for a true patriot to see how China’s strongman politics have torn apart friendships, families and partnerships inside China, and now spreading to Hong Kong. Has the experiment of unification burst?

China’s experiments are not limited to Hong Kong’s politics, economy but also linguistic preference. In the past four decades, China has launched a number of experiments in the mainland as well. When China opened its door to the world for foreign investment and cultural exchange in the 1980s, learning English was considered a necessity for Chinese people to communicate with the world. Private schools that experimented with bilingual curriculums mushroomed in big cities. Now, China has grown up economically. In the annual “Two Sessions” political gathering this March, Chinese lawmakers proposed to remove English as core subject in the nine-year mandatory education. Will someday in sight the experimentation of free trade in China’s Special Economic Zones also to be removed?

Surely, there is one experiment that is not over yet in Hong Kong. That is learning Mandarin in the city’s primary and secondary schools. Hong Kong job seekers seek competency in Mandarin, also known as Putonghua, China’s official language, in order to compete with the Mandarin-speaking mainlanders in Hong Kong and in mainland China. Many schools in Hong Kong teach in English or Mandarin, rather than Cantonese, which is the mother tongue of nearly the entire population of Hong Kong. I did hear more people speaking Mandarin in Hong Kong when I last visited the city. I wish it’s a good sign of diversity instead of a sign of linguistic marginalization. Guangzhou, which is the origin of Cantonese, sheds light on the dismal fate of Cantonese impacted by China’s nationwide “Speak Mandarin Campaign” and domestic migration spurred by economic growth.

I’d like to compare the relationship between Cantonese and Mandarin in Guangzhou to the relationship between a host and a guest. Cantonese is supposedly the host writ large in Guangzhou. Nevertheless, the influx of non-Cantonese speaking immigrants to Guangzhou in the past 40 years has significantly shifted the relationship. Language preservation and pertinent law enforcement has been weak. As a result, Mandarin is the dominant, arrogant host in its adopted home Guangzhou. Cantonese is now the guest nearly to be forgotten. Will Hong Kong in the near future become another Guangzhou in terms of language preservation? While Mandarin is rising, English is fading quicker than Cantonese in Hong Kong. It is a linguist’s nightmare when diverse languages in a place become politicized.

Globally, every cooperation between countries is an experiment. The transfer of power in democratic governments brings a new hope and opportunity for these experiments. But the world is losing patience with China over the experiment of an open economy. China has not become more democratic, or at least more transparent, as the Western world had hoped after China joined the WTO and became more engaged on the world stage. On the contrary, China is a testament to a non-democratic model that seems to lead in strong economic growth and strongman governance. But China is already in the game of a free market with the world. The Belt and Road Initiative is one of China’s ambitious experiments of expanding its global influence.

To some extent, the large public companies in America are running a similar model whose supply chain planning is synonymous to China’s central planning. It is not hard to understand why the Big Four U.S. tech companies are unhappy about the antitrust laws applied to them just as Chinese Communist Party is so assertive with its absolute leadership of the country. Obsession of power is universal by those who already have it. At least the America Inc. strives for accountability and transparency whereas its Chinese counterparts are required to be more patriotic. Patriotism over profit is a norm in China, isn’t it?

A multi-stakeholder experiment requires a back-and-forth exchange of ideas and consultation. Sadly, the world is lacking the atmosphere for experiments. One of the ingredients of doing experiment is academic freedom and business freedom. China cannot cultivate its Elon Musk unless it has such ingredients. The U.S. has a lot of catching up to do as well. According to an annual report of global economic freedom in 2020 by Cato Institute, the U.S. fell in 2018 in most areas of economic freedom including the soundness of money, rule of law, trade openness and regulation.

Another ingredient in doing a large-scale experiment is reasonably cheap labor. Project financing is a headache for any startup regardless of industry and nationality. Perhaps that is why Southeast Asia has an investment boom not only from domestic investors but also from foreign ones like China and the U.S. Chinese business people are doing what the American counterparts did in the 1980s-90s—outsourcing low-end-labor-intensive tasks abroad or the introduction of automation on the laborious work. The U.S.-China trade war benefits countries like Vietnam, Indonesia and Taiwan. On the one hand, China wants to decouple from U.S. tech; on the other hand, China leads the world in manufacturing of steel, car parts, chemicals, electronics and robotics. China is part of the global supply chain and manufacturing accounts for a large portion of the country’s GDP. How to complete an experiment if some ingredients of it have to be obtained through international trade, which today sensitively touches the scope of national security among countries?

Has the experiment of interest-based negotiation surrounding China come to an end? Can China independently do its high-tech experiment with Chinese characteristics? Can the U.S. catch up with its allies with multiple experiments that built on trust? Can Hong Kong’s pre-national security law city image return its luster under the influence of China’s economic experiment with the Greater Bay Area? If you’re like me having an experiment with the future, stop yourself from jumping to conclusions might let the chemistry last longer.