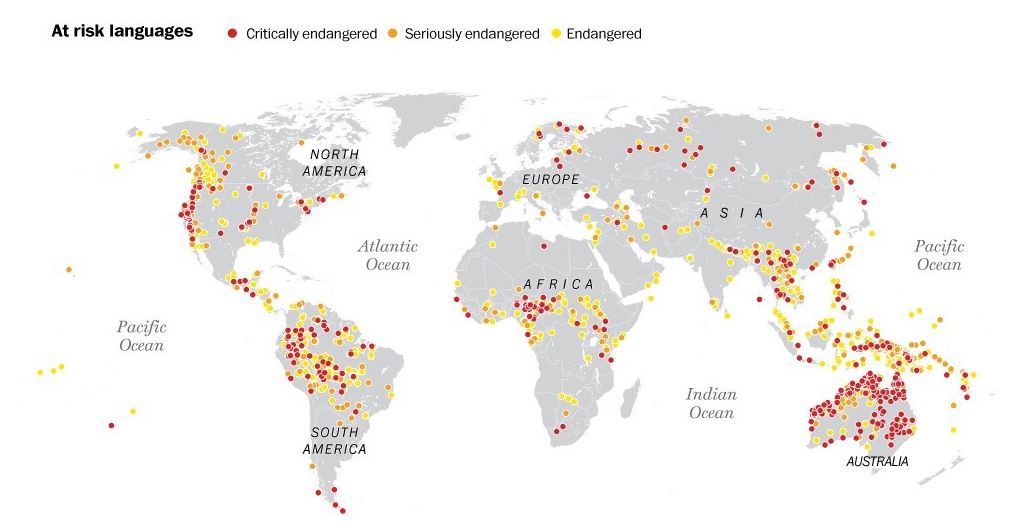

What is linguicide? It’s a blend of two words, linguo– and –cide. It means the death of a language, either naturally or from political causes. My year of saving endangered species and languages in 2020 has risen to the occasion in the Year of Pandemic. I bet Google Translate must be overwhelmed by requests for translating non-dominant languages into dominant languages, and vice versa. Reports show Google Translate supports only 100 languages, give or take. There are about 7,000 languages spoken in the world. Half of the population in the world speaks 50 languages, and the other half of the population speaks the remaining 6,050 languages. By the end of this century, it is estimated that half of the 7,000 languages will fall into silence. Linguicide indeed.

This is not my baseless speculation. I say it as a translator, so does linguist Mandana Seyfeddinipur. I remember when I defended my creative writing thesis a decade ago, I told my professors that even though I wrote my Chinese stories in English, there were nuances unique to the Chinese culture that could not be translated. That sparked the interest of my professor who was fascinated by East Asian culture. Until today, I still cannot be sure I find the right word to express myself both verbally and in writing. Language is the only feature that distinguishes humans from animal communication. Animals don’t understand human languages but humans can interpret animal communication through animal behaviors and can communicate in a shared language.

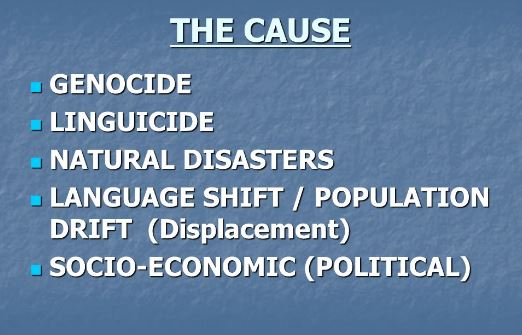

I came across the word “genocide” through historical events. From the Holocaust in WWII to the Kosovo War (1998-1999) and the Rwandan genocide (1994), just to name a few. Sadly, a survey finds two-thirds of young Americans lack basic Holocaust knowledge. I doubt there would be a more promising figure in the same age group for the understanding of history dating back even further, such as the American Civil War and pre-New World in 1492. If political leaders who committed wartime crimes should be held accountable, shouldn’t the actors who kill languages be responsible?

Years ago I watched a movie titled “Lost in Translation.” I was drawn to its title more so than its storyline. I’ve spend a lifetime to figure out why not everything is translatable between languages. Partly because the pronunciation, diction and facial expressions cannot be captured in a target language whose origin does not have the same connotation as the source language. The latest technologies might fill those gaps but still, in my opinion, every language is unique to its own identity and culture. When we are in a foreign land where exotic language is spoken, we only can relate those circumstances to our own experience in order to understand the context. We form a bond in humanity even though we don’t speak the same language.

If we understand that, we will be more open-minded about the fact that meanings are therefore bound to be lost in translations. We should take a grain of salt when we turn to Google Translate for help, especially when one of the two exchanging languages is a non-dominant language such as Cantonese, my mother tongue. We may want to ask more questions from the speakers to explain the meaning instead of resorting to Google or Twitter—we are “downgrading” ourselves as Mandana Seyfeddinipur put it. Yes, the art of language does not appear out of machine learning or the ever-evolving internet language. When one cannot communicate in a language that she feels comfortable to is comparable with an electrical short circuit in her brain.

Language shift resulting from displacement or the speaker’s adoption to a new environment usually lead to the loss of a language. In order to survive, any speaker will have to confront with this painful decision to give up his or her heritage to another language. Globalization, climate change and urbanization are some of the determinators in this decision making.

Globalization does bring us closer by sharing of ideas, cultures, goods, services and investment. That is a major reason why Google Translate has exponential growth because of increasing data feeding and usages by global citizens. The classic reminder for language students is use it or lose it. I haven’t spoken Japanese for a while and soon it becomes a reading language only. If I don’t expose myself to Japanese texts often enough, perhaps it will become a total stranger. I believe the same situation happens in any non-dominant language. Its fate is even direr because many of those 6,050 languages spoken by half of the global population are not written. They vanish without a trace before we notice it. My mother tongue speaks of itself. If I need to write Cantonese literally, I have to borrow homonyms from Mandarin Chinese or from English to capture the sound of a particular word. Imagine those indigenous people who are not literate, how can they capture sound in written form?

Climate crisis displaces wildlife and humans. We may have heard of the term “climate refugees.” Urbanization is another form of migration, the internal migration. Neither migration promotes diversity of language. Our languages reflect our living environment. When we are confronting the loss of biodiversity and habitats, the richness of our languages will lose its luster as well. The “my way or the highway” mentality doesn’t help either. If you cannot accept other’s culture and identity, it’s no different from genocide.

China’s latest efforts to speed up the assimilation of its ethnic minorities into the majority Han culture have reached Inner Mongolia, following a cultural-revolution-style cleansing of Uyghurs in Xinjiang province. Years ago when I visited Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, the traditional Mongolian script captured my imagination. I thought to myself then that at least the Mongolians had their own written script comparing to Cantonese. Those vertical lines derived from the old Uyghur alphabet carry sounds and melodies of an old culture. An old tune is worth repeating and remembered, isn’t it?

When Han Chinese are traveling to Tibet and Xinjiang to chase their dreams of seeing a wonderland, they may not notice the draconian language rules for Tibetans, Uyghurs, and now the Inner Mongolians have further eroded these underprivileged ethnic groups in China. I think of my trip to a gallery in Hanoi some years ago. I learned that many ethnic groups in northern Vietnam actually have their cultural heritage from southern China. That explains why a cluster of endangered languages dotted on the map of endangered languages in the region. If you’re interested in contributing to language preservation, a worldwide collaboration called the Endangered Language Project is a good resource.

When I look at the NAT GEO calendar of 2021 that shows two different globes—one is a blue planet, the other is a fire ball resulting from global warming, I can’t help thinking what can be more horrifying than a language massacre. If climate change is a political topic and global warming is due to human activities, aren’t we the actor responsible for linguicide?