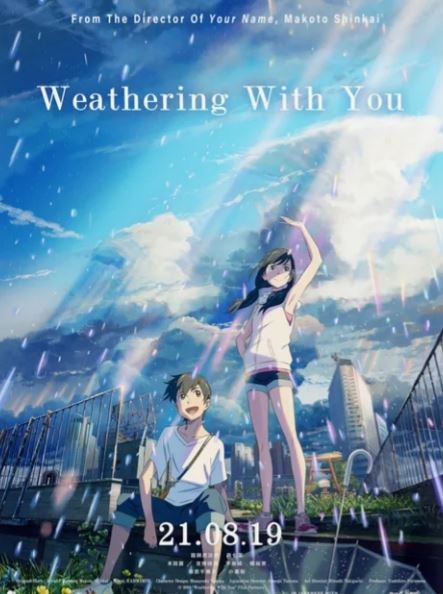

Strictly speaking, Weathering With You (天気の子), “tenki no ko” in Japanese, is an animated feature film written and directed by Makoto Shinkai (新海誠). The story was set in Tokyo during a fantastical period of exceptionally rainy weather. The teenage “Sunshine Girl” named Hina was the “child of weather,” as the Japanese film title suggests. Hina had that magic to stop rainy days and bring temporary sunshine back to the Tokyo sky.

Hina was a poor orphan with a younger brother named Nagi. To support the family, Hina worked at a McDonald’s store in Tokyo, where she met her destiny love, Hodaka, a high school boy who left from a rural village for better opportunities in Tokyo. Their connection started from a complimentary Quarter Pounder at McDonald’s. Employee Hina secretly gave homeless Hodaka, who sheltered in the store from the rain, something to eat. What a praise to the American franchise for making this Japanese romance possible!

Right there, the scene reminded me of the homeless people in Hong Kong. Few people are aware of the charitable role these 24-hour diners and restaurants play after midnight. Especially in affluent cities like Tokyo and Hong Kong, as long as the homeless people are well-behaved, they relocate from one fast-food restaurant to another to find temporary hideout for the night. Looking at Hodaka on the screen, I associate with poverty. And that’s exactly what director Shinkai wants to express in his work—youth poverty in Japan.

Last year’s top-rated movie Parasite has also touched upon the theme of wealth inequality and poverty in South Korea. As Director Shinkai of Weathering With You said in an interview that social stratification is obvious in Japan. I second that for the situation in China, and in the United States, too.

In the movie, two poor kids, Hodaka and Hina, fell in love with one another and they lived on Hina’s magic power to make both ends meet. And yet, the day did not last long. The more Hina prayed for a good weather, the less of her was seen in a human body. She would evaporate like water and eventually disappear! Tokyo returned to the days of torrential rain. Th deluge put a third of the city underwater. Where is the “Sunshine Girl”? Where is the normalcy of weather?

Many Japanese anime fans like me understand that Shinkai has hinted the climate crisis—“気候危機” in Japanese—throughout his movie. I remember there is a scene in the movie: some years later, the old lady who used to be Hina’s weather client for a good weather to worship the spirit of her late husband told Hodaka that, many many many years ago, Tokyo used to be submerged in water resulting from typhoons and natural disasters. When people inhabited this place and adapted to the changes, they made it into a prosperous city. And now the continuous raining days were back, and the city was once again returning to what it used to be.

Let’s not question whether the old lady’s fictional storytelling is true in reality. Let’s just think about how Japanese people react to climate change. According to WIRED, the orderly society like Japan where people are respectful toward one another, ordinary people tend to be submissive rather than vocal about big social issues like climate change. Instead, similar to harmonious Confucianism in China, Japanese Zen spirit calls for bringing peace to your soul and making peace within as well as with your surroundings.

As Meera Subramanian, president of Society of Environmental Journalists, said beautifully, “Environmental stories are front-page stories. They’re every-page stories. They’re everywhere stories and they’re everybody stories.”

Climate change is everywhere and about everyone.

Viewers see a movie to look for entertaining pleasure. And Weathering With You does not disappoint me in that aspect. Moreover, the film somewhat surprises me that this is more than just an animated feature. It reflects Japan today. There is an underlying shock from social stratification and climate change in Japan. This is how Shinkai said it in his own language during an interview with the United Nations:

“(『天気の子』の)根底には気候危機から受けた衝撃もあることを観客に知ってもらえたら、とても嬉しいです」”

This is Google Translate version edited by me:

“I’m very happy if (the movie) lets the audience know that there is an underlying shock from the climate crisis.”

Perhaps we should be hopeful that there is a subtle calling among Japanese youths for change—Japan’s wealth inequality needs to change, so is the country’s climate crisis apathy.

Environmental stories are front-page stories. They’re every-page stories. They’re everywhere stories and they’re everybody stories.

—– Meera Subramanian, SEJ president

Wanna leave a comment? Click here.