In no one’s world, different kinds of political systems will have their strengths and weaknesses. The author made a very good point about how we should respect other cultures and religions and seek interest-based cooperation. He wrote, “The West’s willingness to embrace a more inclusive conception of legitimacy—one based on responsible governance rather than democracy—would certainly help widen the circle of nations ready to stand against countries that are predatory toward their own citizens and threatening toward the international community. (Kupchan, p.191)” With this piece of advice in mind, the US may re-establish leadership in climate action with China, whose political values are contrary to those of the US. This might be accomplished only if the US were in the good hands of competent leadership.

The benefits of US-China collaboration outweigh its drawbacks. As Bill Gates said, the interdependence between the US and China can lead to more dialogues and mutual understanding. Businesses regardless of nationalities are often drawn to secure environments where either accountable leadership and/or stable economy are nourished. China has the efficiency that American entrepreneurs crave whereas the US has a high degree of market transparency that Chinese investors admire. If the world’s two biggest economies collaborate based on mutual interests, when one partner is “under the weather” like what we are seeing now in the US leadership, the other partner could be perceived as a functional part of a working machine, if you will, to get the world’s economic activity going.

Well, China has just done that. It is on the track of economic recovery toward green economy. Among the big emerging markets, China is an assurance for global investors and rating firms. China’s green bond market has expanded at incredible speed since opening in 2015. Last year in the fourth anniversary of the New Development Bank, formerly referred to as the BRICS Development Bank, the bank plans to increase the stock of green infrastructure in its portfolio, which involves prioritizing investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable waste management and clean transportation. This May, China has excluded “clean coal” from a list of projects eligible for green bonds. If the US welcomes a green economy to create jobs, reduce wealth inequality while adapting to climate change, China’s partnership is only complementary but not contradictory.

In No One’s World, the author gave a brief history of China’s communal autocracy. As a witness of China’s reform of state-owned enterprises (SOE) in two decades, I disagree with Kupchan’s underestimated account of unemployment in the economic reform. He wrote, “China’s gradualist approach to privatization protected employees in the state sector. As a consequence, China did not confront the high unemployment and large-scale dislocations that accompanied ‘big bang’ transitions of the sort that took place in the former Soviet bloc. (Kupchan, p.95)” The author’s source for his statement may have come from an elite background but he obviously had not spoken to ordinary folks like my parents. Tens of millions of Chinese people lost their “iron bowl” jobs. I dedicated a whole chapter in my book, Golden Orchid, to the lost generation in China, among them were my parents.

In addition, in Mr. Kupchan’s account China’s transition to markets and private ownership seems to be too effortless to be true. What about the political upheaval in 1989? What about the sacrifices that ordinary Chinese have contributed to the country’s glory? How much land grabbing took place? How many lives were lost in profit-chasing, shoddy projects? One thing to note. What we see as the status quo of legacy admissions in leading universities in the West is also seen in China. After all, not everyone can be enrolled in Peking University and Qinghua University, the Chinese equivalent of Harvard and Yale. The Chinese elites that dominate renowned Western universities are more or less from nouveau riche families or associated with hereditary socioeconomic privileges in China. Their impression of China might be fragmented and even tantalizing to the Western readers. There’re many reasons that Chinese middle class appear to be satisfied with their status quo. Mr. Kupchan should have looked into how education about the party was instilled in Chinese people’s mind since their coming-of-age years. Chinese people don’t have a state-recognized religion but worshiping the party doctrine certainly plays an important role in social mobility.

In no one’s world, any country can be a trendsetter. China can be one partly because it welcomes international cooperation in research and development. China’s state-led “Made in China 2025” has overturned Kupchan’s statement that the country “tends to copy Western technology, not to improve upon it. (Kupchan, p.103)” China is demonstrating to the pandemic-ridden world how to keep its economic recovery green and sustainable. Shenzhen, a southeastern city adjacent Hong Kong, has become the first Chinese city with full 5G coverage. While China doesn’t encourage immigration, it is opening its doors to foreign talents, investments and cooperation. On the contrary, the US is closing its doors to immigrants, who in the past have contributed to its development.

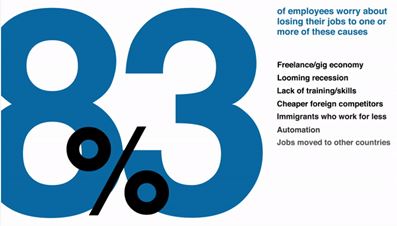

Americans need to be worry if the country’s legal immigrants continue to shrink. Not because how many local jobs are taken by immigrants or lives are lost by immigrant felons, but because American population is aging and productivity is declining. According to World Bank, the US fertility rate, that is, the number of children that are projected to be born to a woman in her lifetime, has declined in 10 of the last 11 years since 2007. The rate was 2.12 children in 2007, falling to 1.73 children in 2018, the latest year that the data has been calculated. For the population in a given area to remain stable, an overall total fertility rate of 2.1 is needed, assuming no immigration or emigration occurs. America falls behind the mark.

The US is a melting plot as immigrants equate the cultural assimilation and acculturation with Americanization. The US is a nation built by immigrants and their descendants together with indigenous people in the American continent. Ideally, the US should do better than homogeneous countries (e.g. Japan, Iceland) to respect and understand other beliefs and values while upholding our identity as a nation. Kupchan pointed out one of the great assets of liberal democracy is “its capacity for self-correction.” He wrote, “Political accountability and the marketplace of ideas have regularly helped democracies change course. (Kupchan, p.166)” Immigrants have enriched our economy and society. “The marketplace of ideas” lies in diversity and inclusion.

Furthermore, climate change does not respect borders and it is altering migration patterns, both humans and wildlife. It can only be solved with cooperation and collaboration across borders and worldwide. Perhaps climate change has induced good timing on which Kupchan emphasized as an ingredient to modernity for different societies. The author called for “pragmatic partnerships, flexible concerts, and task-specific coalitions” amidst renationalization of politics in Europe and partisan polarization in the U.S. I find these are all good strategies for global leaders to strike a balance between development and sustainability, between self-interest and the common good in no one’s world.

“If the West can help deliver to the rest of the world what it brought to itself several centuries ago—political and ideological tolerance coupled with economic dynamism—then the global turn will mark not a dark era of ideological contention and geopolitcal rivalry, but one in which diversity and pluralism lay the foundation for an area of global comity.”

Charles A. Kupchan