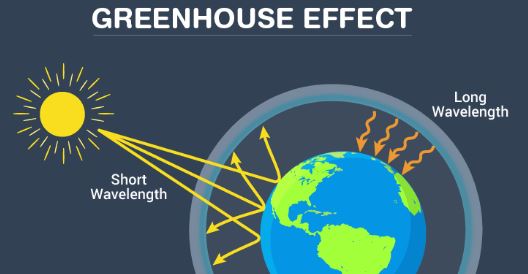

Do you know what is the greenhouse effect? Have you heard of Eunice Foote?

When I was working on my sustainability coursework, I happened to discover that Eunice Foote was the first female scientist who discovered the greenhouse effect more than 150 years ago. She spearheaded modern climate science even a few years before her male colleagues did in the 1850s. Her legacy reminded me of astrologist Henrietta Leavitt who preceded her male colleagues in the Harvard Observatory to discover the fluctuation brightness of new variable stars which led to the mapping of the Milky Way and beyond.

I was so excited at my discovery of Eunice that I interjected “Eureka!” literally as exuberantly as Archimedes who rose naked from his bath tub. Water receded as Archimedes lifted his body out of the bath tub; my phone flopped off my fingers when I read with elation about Eunice’s remarkable legacy.

A couple days after my learning curve was bent over Eunice Foote, the Overlooked obituaries series in the New York Times also paid tribute to Foote. My learning curve rebounded. Using glass cylinders, each encasing a mercury thermometer, Foote found that the heating effect of the sun was greater in moist air than dry air, and that it was highest of all in a cylinder containing carbon dioxide. As Foote wrote in her 1856 paper:

“An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature. . . must have necessarily resulted.”

Eunice Foote was not known to the public at that time mainly because women were deliberately overlooked by men in the male-dominant science world. Her discovery paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) on August 23, 1856. But she did not present her paper. A male colleague named Joseph Henry did it on her behalf. Neither Foote’s paper nor Henry’s presentation of it was included in the conference proceedings. What’s more sexist, in modern language, three years later, John Tyndall demonstrated more sophisticated experiments to verify and improve Foote’s finding. In his publication, Tyndall gave credit to male colleagues such as Mathias Pouillet for his work on the passage of solar radiation through the atmosphere, but didn’t mention Foote. Roland Jackson, a biographer of Tyndall, believed that Tyndall and other physicists of the time probably did not know of Foote’s work.

I reserve my skepticism. The presentation at AAAS to climate scientists is like making a speech at the Oscars to actors and filmmakers. Despite that Foote’s work and her presenter’s name were forgotten in AAAS’s history, Foote’s discovery was not only verbal but it was written as well. There isn’t even a known photograph of her today.

The more I learn about American history, the more similar stories like Foote or Leavitt I encounter. It is hard not to view gender difference, both biologically and socially, as a deciding factor to understand the world we are living in. I grew up with Chinese history dated back thousands of years. It’s interesting to me that in the many, many years before China and the US formed diplomatic ties in 1979, women weren’t equally treated with men in both countries. Patriarchy was an innate social system in many countries long before global trade or cultural exchange. I come across in literature quite a few synonyms of male dominance such as male chauvinism, male superiority, misogyny and many more. In Chinese monarchy history, there was only one female emperor, Wu Zetian, who happened to be in the Tang dynasty (618-907 C.E.), the most prosperous and affluent dynasty in history. I don’t like using empress just as female actresses regard themselves as actors. Without an open and stable society in the Tang dynasty, a woman monarch would have been a pipe dream. But at least, China is ahead of the US in the score of female leadership.

Eunice Foote was more than a climate scientist. She was a women’s rights advocate. Seven years before her scientific paper, Foote was present at the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, on July 19-20, 1848. She was one of the signatories of the Declaration of Sentiments. I see this document as significant to the development of the women’s rights movement in the US as the Declaration of Independence was to the country’s founding history.

I appreciate that the New York Times recognized that its renowned obituary section needs to be inclusive. As the paper wrote in the introduction of the Overlooked series: “Since 1851, obituaries in the New York Times have been dominated by white men. Now we’re adding the stories of other remarkable people.” Had Eunice Foote not lived a remarkable and influential life, perhaps she would never have been in the New York Times obituary.

Think about those 70,000 plus souls in the U.S. who have died in the COVID-19 pandemic. If obituary writing is more about life than death, a testament to a human contribution, how many pages of overlooked obituaries should there be to amplify the narrative of this tragic disaster of humanity?