During my deep dives in a sustainable retreat, I find it amusing that we have a rigid dichotomy between science and mysticism. But quantum physicists are enthusiastic to demonstrate the experiment of quantum entanglement. (I’ll leave the powerful search engine to explain for you what is quantum entanglement. It’s easier to understand the physical phenomenon if you watch the video experiment for beginners.) Some claim quantum physics may help us to explain spiritual phenomena. If spirituality can be scientifically proven, does it mean spirituality is no longer a myth?

In other words, may I argue that scientific fundamentalists are no different from religious fundamentalist? They both have unwavering beliefs that their doctrines are the ultimate truth. With the continued debate and counter-debate of quantum physics, how can we not appreciate that human beings are a unique species that can cross disciplinary boundaries to seek truth?

An interesting discovery delighted my ignorant mind. With the help of advanced technology in medicine, researchers have sequenced 64 human genomes which include individuals from around the world. The new reference data can be helpful to the development of personalized medicine, where the selection of therapies is tailored to a patient’s individual genetic background.

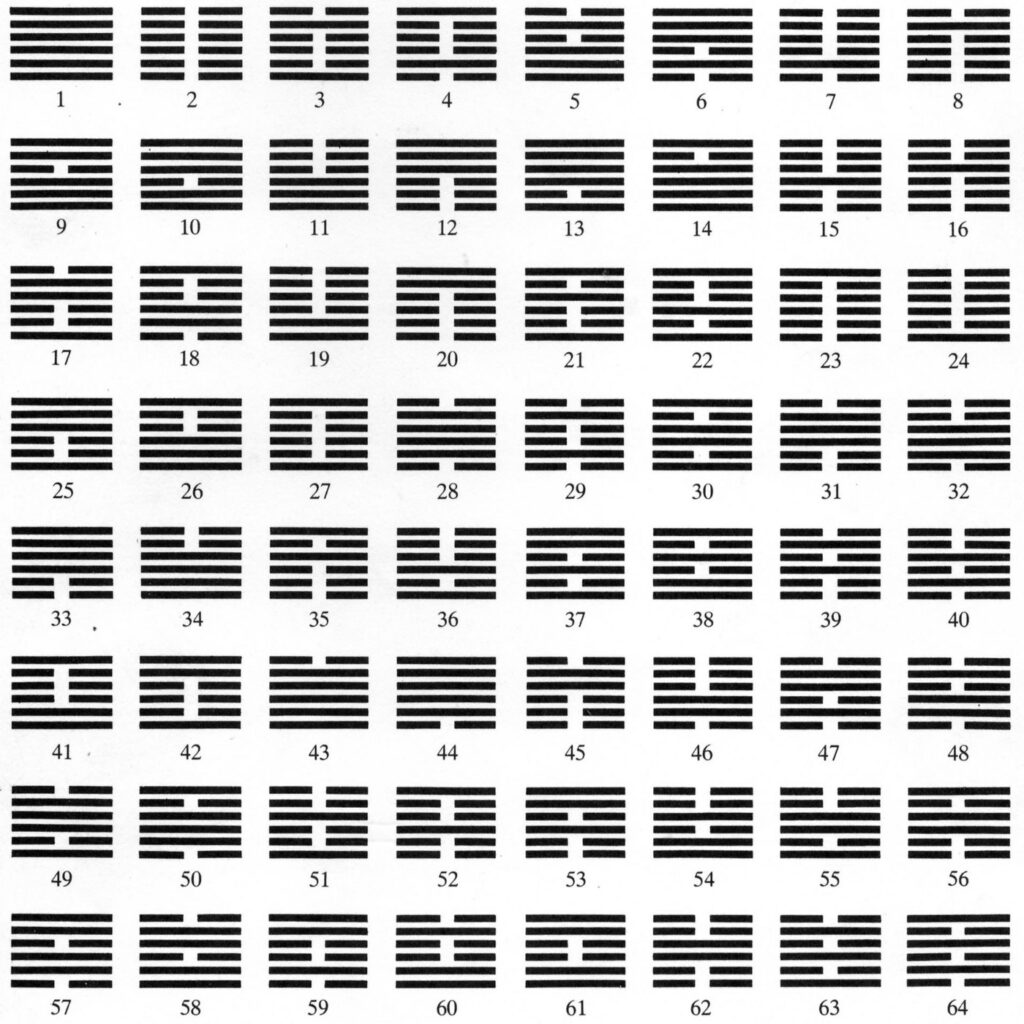

In ancient Chinese classics, a book called “Yijing (I-Ching),” 易經 in Chinese language, has been translated into many languages and played an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought. The Chinese classic work published in late 9th century BC is also called “The Book of Changes,” in which the hexagrams are arranged in an order to provide guidance for moral decision making. There are 64 hexagrams of the “Yijing (I-Ching).” Chinese scholars noted that these 64 hexagrams were closely coherent with the 64 human genomes in sequence.

The book, Yijing (I-Ching), has greatly influenced many branches of Chinese knowledge, including Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), philosophy and astrology. It took a long time for the quantum theory to be established, accepted and become a popular field of study. Like the fate of quantum physics, TCM is not widely accepted until recent years. TCM is even harshly criticized by Western scientists, media and environmental watchdogs.

The row over the negative impact of TCM on endangered species will not cease until China demonstrates to the world the best practices of sustainable herb cultivation and legal wildlife trade. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), sustainable, legal and equitable wildlife trade can be a powerful nature-based solution for meeting the twin challenges of enhancing rural livelihoods and conserving biological diversity.

Throughout human history, China is not the only country that has a long history of herbal medicine practices. Indigenous and rural communities around the world also rely on traditional herbal medicines for healing and trade. Do you know the fast-growing cannabis farming not only threatens animals’ habitats but also consumes a massive amount of electricity for indoor cultivation? According to Smithsonian magazine, citing Bloomberg Environment, legal cannabis production in the U.S. consumes enough electricity annually to power 92,500 homes for a year. In your wildest guess with the help of your smart device, how much carbon footprint are there for the illegal marijuana sites? If you deem yourself an unbiased environmental watchdog or reporter, do you see the different attitude among critics toward TCM and cannabis farming?

Adding to the drama of anti-Chinese sentiments, the pro-independence Taiwanese lawmakers even proposed to rename TCM as “Taiwanese medicine.” Political-minded critics have demonized TCM as a threat to the lab-based Western medical research. The most common criticism that I read about is TCM cannot produce convincing clinical evidence. My layman’s observation about Western medicine is it’s a school of thought that has no tolerance of abstract thinking and uncertainty. No wonder that so many Chinese medical students prefer studying Western medicine to TCM. Who doesn’t like efficient treatment and quick investment returns? The western centrism also plays a role among TCM naysayers. It must be fearful for them to wear sunglasses in a dark room called echo chamber. Stay tuned for my next essay on the unsolvable problem of maintaining the status quo for the well-to-do individuals, businesses and industries.

I want to point out that “efficient” is different from “effective.” In the healthcare sector, the word “efficacy” is frequently used among medical professionals. As the demand for self-care increases, effective communication between healthcare provider and patients is paramount. You’ll learn more about my insight about TCM and palliative care in my memoir, “Golden Orchid“. The most effective medicine in my experience and also championed by Dr. Bernie Siegel is love.

How much you love others reveals how much you will be loved. There is no love drug to prescribe or sell over the counter. Love comes from within.

Socrates and Confucius never met. Both sages made a similar humble remark on their ignorance. I begin to think whether this is a balancing loop for human nature. The fewer tools (both tangible and non-tangible) a man has, the more adaptable to uncertainty he is. Whereas the more tools a man has, the less adaptable to changes he becomes. Today we have the smarter-than-us internet-of-things. We are addicted to certainty, which is exactly the opposite of what “Yijing (I-Ching)” calls for. The only permanent constant is the constancy of change. We’re spoiled by instant answers provided by the powerful search engine and mobile phone applications. What if the answers that we are seeking have no absolute answers? What if the answers reflect the constant flow of changes in our unknown world?

Unlike in the physical world, there is a formula to a chemical reaction and deductive reasoning for a hypothesis in science. In humanities studies, objectivity can only go so far. Of course, this is purely my opinion based on my knowledge, experience and personalities. My subjectivity determines how I perceive the physical world. No matter how objective we try to design and apply technological tools to understand the unknown world, we cannot remove our own subjectivity from everything we see and do. Not to mention that our invisible inner world changes. We only pay so much attention to the visible physical world.

Data itself has no meaning. We give meaning to the data based on how we want to use the data. To some extent, data analysis is a customized hype that boosts the human superstitions of certainty. Thus, as much as we emphasize data use, data can unite us but data also can divide us or make no impact.

We are so good at labeling. The digital of almost everything perhaps propels our labeling fallacy at an even higher speed. That’s why the more I dig into this rabbit hole of social phenomenon, the more determined I am to stay away from news outlets, institutions, civil society groups, individuals and ideas that have become the by-products of data hype syndrome. If you faithfully trust only numbers and algorithms, you’re akin to silicon being with binary thinking.

Come to think of it, as Pope Francis famously says, “Who am I to judge?” Silicon being or not, this is the fun of living with uncertainty. I embrace science. I’m also aware of the gray area of our world that STEM disciplines cannot detect and explain. But our digitalized society will produce more STEM-based fundamentalists. It’s about time I learn to communicate with silicon beings in my sustainable retreat. When the speed of civilization development outpaces the Earth’s self-regulating system to repair and reinvigorate the conditions for life on the planet—that is the Gaia theory, humanity will have to adapt to a possible inhabitable condition to survive. The Covid-19 pandemic is a test run for our adaptability to uncertainty.

“The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.”

—Socrates (c. 470–399 BC)

“Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” (「知之為知之,不知為不知,是知也。」)

—Confucius 孔子 (c. 551-479 BC)

(To be continued)