When I wrote my book proposal for my memoir, Golden Orchid, I couldn’t think of a more powerful sentence than describing my book as a personal account about “an extraordinary life of an ordinary one-child family in contemporary China.” Ordinary life always motivates me to ponder, to listen, to sob, to smile, to write, to remember, to love, and to help them when help is needed. Ordinary life greets me from the window of my home office every morning. Ordinary life keeps me going against all odds and also keeps me up at night. As I wrote in my first essay of this series, as a sustainability professional, I’m aware of ordinary life of both human and non-human. Two recent incidents that have an impact on ordinary people have disappointed me. I find them good case studies to pinpoint the importance of effective communication in my sustainable retreat. So, I’m about to share some insights in the following two essays.

The first incident is that a Washington-based science organization provides non-governmental groups with its open source database in a partnership program to monitor China’s oversea coal-fired power plants. I find it upsetting not because the data is being used for promoting government accountability. It’s because the science organization claims to be apolitical. The organization’s affiliated partners, however, are critical of, and even demonize China’s pledge to stop building coal-fired power plants beyond its borders.

I’ve written it in my previous essay that we only pay so much attention to the visible physical world. Data itself has no meaning. We give meaning to the data based on how we want to use the data. If you believe you’re an objective educational source of climate change or an objective source of citizen journalism, do you notice that in comparison with climate action efforts between China and India—both are developing big countries in terms of land and population—China seems to bear the brunt of the name and shame approach in the Western politics, media and now academia? India and, as a matter of fact, the entire South Asia is much lesser discussed or mildly criticized by the same group of self-claimed independent think tanks, organizations and media outlets.

In my view, quite a few non-Asian people, and even some second-or-third generation of the Asian diaspora, have little knowledge about the history and culture of pre-Communist-ruled China and pre-colonial ancient India. I have Chinese parents and was born and raised in China, but I still can’t be proudly say I know about China more than an American citizen knows about the US Founding Fathers and Mothers. When I was a graduate student studying writing in Pittsburgh, I learned that some of the great works of American literature that I knew were banned books in the school districts of my classmates in their home states. Preserving literature is what I can, and should, do.

Knowing your ignorance before you make your opinion about other’s wrongdoing is my way to coexist with differences and embrace inclusion. I do not want to disclose the name of this science organization. I’m not a name-and-shame divider. I believe when it comes to climate change communication among big countries, name-and-shame approach only widens misunderstanding, increase hostility and deepens mistrust.

During my job search and my lifelong study about mindful living, I’ve learned many lessons. The most important takeaway to me is how to communicate with others comfortably and effectively. Non-governmental organizations have done marvelous work to educate the public about natural science and also influence government officials to implement timely policies. And yet, I don’t rule out the possibility that some organizations are struggling between what is the right thing to do for a sustainable retreat and what their donors want the funds to be spent differently. My informational interviews helped me understand the not-so beautiful side of civil societies. The dilemma of making sponsors happy or not seems to have troubled career professionals not only in civil societies but also in private businesses and the public sector with their different stakeholders. In my view, no one can summarize the issue so poignantly as scientist and author, James Lovelock, does. Allow me to quote an excerpt from one of his works about the Gaia theory. He wrote:

“Even more than this, scientists today are hampered by their low social and economic status. Long gone is the respect and independence given to Lavoisier, Darwin, Faraday, Maxwell, Perkin, Curie and Einstein. Hardly any laboratory scientist anywhere is as free as a good writer can be. Indeed I suspect that the only scientists we know well are those who can write entertaining books; the real contributors to knowledge are mostly unknown. Younger scientists cannot freely express their opinions without risking their ability to apply for grants or publish papers. Much worse than this, few of them can now follow that strange and serendipitous path that leads to deep discovery. They are not constrained by political or theological tyrannies, but by the ever-clinging hands of the jobsworths that form the vast tribe of the qualified but hampering middle management and the safety officials that surround them.”

The science on the human contribution to global warming is crystal clear. But has anyone thought about minimizing human-caused miscommunication of climate change? Miscommunication leads to inaction of climate change. In my view, the consequence of miscommunication is worse than the consequence of data error in climate science. Data error is traceable and fixable within human’s knowledge and power. Information that is mistold for a self-interest purpose cannot be rectified. Scientific data that is used for political and financial gains is valuable but controversial. This is partly why I’m mesmerized by the power of language in the face of science and conscience. A piece of scientifically-proven fact sheet can be read differently by different people with different intentions. The example of a science organization and its partners was exactly what I see as hypocritical.

I’m about to put you into a situation to explore effective communication. You may part ways with me here if you believe being a Hawk can make world’s top greenhouse gas emitters do their due diligence in climate action. I wish you unsuccess and world peace.

Suppose you meet two apple sellers you don’t know. Seller A’s stand attracts quite a few people but most people only inquire and then leave. Seller A is anxious to sell her apples but she is getting annoyed when you ask her about the price of apples. She talks to you harshly as if holding a knife at your throat. You stop at Seller B’s stand for the same inquiry about her apples. Seller B is also anxious to sell her apples. She wants to go home early if her apples are sold out. Seller B has an eye for her prospective customers. You leave her an impression that you might have good appetite for apples. So she asks you nicely to sample her apple. Will you buy apples from Seller A or from Seller B? Generally speaking, do you prefer listening to someone that talks to you bitterly or someone that talks to you kindly?

I learn from my experience that oftentimes my pitch sells not because how much I care about the subject but what the subject matters to the person who buys my idea. In fact, it’s getting harder to maintain relationships in the era of attention scarcity, resulting from an overriding push by corporations and institutions to capture and mobilize attention. To some extent, the internet puts every user into a make-yourself-comfortable cocoon. It’s more difficult to leave a deep impression to a stranger on the internet than with a handshake or having a cup of coffee in person. Speaking of binary thinking and data-centric blind spot, teleconferencing can relieve some immediate communication hiccups. It cannot resolve interpersonal conflicts and handle misunderstanding as effective as constant in-person dialogues.

Human activities are increasing the concentration of greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere. Human activities including our thoughts and deeds also cause miscommunication and mistrust in climate action. When it comes to intergovernmental climate change communication, name and shame approach does not sit well with the violators, especially with great powers. A negotiable merit-based bilateral agreement may be worthwhile. A change of “gotcha” tone and an exchange of handshakes may help Seller A sell more apples and attract more customers. By studying the primates’ behavior, I bet a majority of human beings, like their cousins, prefer carrots to sticks.

Furthermore, speaking of global efforts in reducing carbon emissions, I don’t know aside from the big countries and the EU, where else in the world one can have the relatively might in finance, technology, market and government to experiment with carbon pricing policies? Carbon pricing policies are new to our fossil fuel-dependent world. They involve many stakeholders. But we’re running out of time to make an ideal mechanism before implementing them.

With respect to climate mitigation and adaptation, whether you’re a critic with good intentions or a troublemaker inciting US-China hatred, experimenting with new things and fine tuning them along the way might be better than finger pointing at the doers for wrongdoings, no? Wouldn’t it be more encouraging to spread the can-do spirits by comparing accomplishments and sharing successes? Instead of weaponizing data to shame a big country whose ordinary people are the most innocent in any war of ideas, will it be more constructive if environmental watchdogs publish regularly the fact-based progress of the big greenhouse gas emitters by self comparison in a given period?

My sustainable retreat widens my horizons. In my learning of non-governmental organizations and 503c organizations in America, I find these entities are fighting for their respective war of ideas as well. Whether you’re an individual or an organized groups in China or outside China, if you don’t like China, you are entitled to your opinion. If you don’t like the U.S, I also agree to disagree. At least I know these two great powers can determine the destiny of other small low-lying countries in the face of sea level rises. At least I know the pandemic has impacted the world’s human population. Together with ongoing rapid declines in biodiversity, time works against us to change course for a sustainable retreat. If you want to break down a big house, shouldn’t you have a plan about what you are going to do with that land before you demolish the property? Frankly, if big countries can listen to others, there won’t be an arms race, space race, tech race and history would have been rewritten.

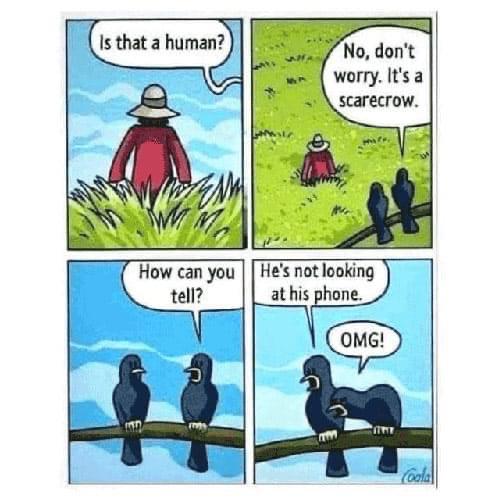

If I have to find a scapegoat to blame, I blame our indifferent, human-imitation, internet-of-things. Their algorithms are full of 1’s and 0’s, ignoring uncertainty. No wonder ordinary people’s minds are polluted with binary thinking. The longer we spend our time on the smarter-than-us devices, the more likely we think alike. Aha. The phenomenon reminds me of the old saying, “Birds of the feather flock together.” Humans are emotional creatures. The stronger humans are attached to their devices, the deeper trust humans will develop into technology. Technology is a powerful tool. The adjective “powerful” is relative to my ignorance of technology. I’ve learned to embrace my ignorance to ask better questions in my sustainability retreat. Can technology do that? Without knowing the reference basis, an adjective means more to the speaker than to the listener. This is why I reiterate that the algorithms in our digital life may overlook the immense ocean of what we called the “gray area.” I still uphold my assumption.

(To be continued)