Lately I’m struggling with the solutions to better reduce, reuse and recycle the plastic take-out boxes and plastic bags in my house. As responsible consumers, we agree to cut back on plastic waste by action. Despite voluntarily reusing shopping bags and plastic containers, we really cannot yet influence retailers and manufacturers to reduce the use of single-use plastics for packaging and transportation. While I was looking for best practices online, the powerful Google search engine introduced me to “Solutions Journalism.” I was like finding my own oasis to incorporate problem-solving facts with my global sustainability advocacy. Solutions journalism is the way to go in this transition period from a fossil fuel-dominated energy world to one that offers equal opportunities and renewable energy sources such as solar power, wind and biogas. Solutions journalism is what today’s mainstream media and grassroots journalists need to build a circular economy.

As opposed to circular economy, we’re living in the broken system of linear economy which traditionally follows a “take-make-dispose” industrial model and business practices. Do you remember there was a time we only used glass milk bottles for fresh milk? The milkman would recycle those used bottles and refill them with fresh milk. In London, the retro style milk truck returns (video click here). Customers bring their own bottles and containers for milk and food. The vendor delivers the products door to door basically in their naked (unpackaged) form.

How nice to have a plastic-free zone in a supermarket to experiment with the idea of zero waste. Zero waste is possible. A remote village named Kamikatsu (上勝町) in Japan has spent 20 years practicing just that. With a population of 1,300, villagers must separate their household waste into no fewer than 45 categories before taking it to a collection center. Those that are reused such as clothes, crockery and ornaments end up at a recycling store for the next user free of charge. These are best practices of a circular economy for us to emulate and expand for the far-reaching benefits of zero waste.

According to Solutions Journalism Network, solutions journalism is not only for aspiring and veteran journalists but also for concerned citizens who love great journalism. The journalism industry certainly needs a shakeup from bottom-up to top-down to regain public trust. Especially in the U.S. whose societal institutions—government, business, NGOs and media—are all suffering trust crisis over a growing sense of inequity. So what is good solutions journalism? It must meet these four ingredients:

1. Can be character-driven, but focuses in-depth on a response to a problem and how the response works in meaningful detail;

2. Focuses on effectiveness, not good intentions, presenting available evidence of results;

3. Discusses the limitations of the approach;

4. Seeks to provide insight that others can use. That is, the reporting should draw on sources with ground-level understanding.

Simply put, it is a way of journalism to cover more than just problems. How the problems happen and how to solve them are equivalently important. In the information-overloaded Conceptual Age, we often find ourselves lost in the sensational headlines and hypes from various media outlets and from our family and friends’ social media accounts. We don’t even realize we’re living in echo chambers. We have no shortage of knowing what’s going on near us or ten thousand miles from us. We also have no shortage of solutions. But we’re short of credible solution sorters to comb through reliable data and empower us with knowledge in order to better our well-being.

Besides, what more can we ask the government to do for us if we aren’t well-informed what the options are? Oftentimes the poor and the disadvantaged don’t even know they are being taken advantage of by the powerful and the privileged. For example, if you know the negative effects of an incinerator, will you be supportive of a facility to be built in your neighborhood? But what if you don’t even know what a facility is for in your neighborhood until you’re diagnosed with a lung cancer resulting from taking in excessive polluted air from that facility? Do you know more than 99% of plastics are made from fossil fuels, both natural gas and crude oil? Do you know that not until we hold the oil and gas producers accountable can we entirely resolve the plastic waste problem? Believe or not, ExxonMobil is taking action to address plastic waste by increasing plastic recyclability in plastic waste recovery. How effective will its plastic waste management be? Solutions journalism could play a role to connect the dots here. Currently, there is no U.S. federal law to curb plastic waste and push for a nationwide Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) on end-of-life recycling. Without nationwide legislative oversight of plastic packaging waste and manufacturing, our unrelenting cleanup efforts in the downstream of a linear economy won’t solve the plastic pollution crisis. Now I know I’m hitting a cul-de-sac with respect to the plastic waste problem in my house.

Information does not necessarily become knowledge unless it is relatable and accepted by an individual as being trustworthy. The polarization in the U.S. today is partly because of information confusion and education deficiency. Solutions journalist, a new job title for our Conceptual Age, should be able to inform and educate the general public not only “why” but “how” to better their life in the lens of climate mitigation and adaption. We may disagree a lot but no one in different social class is not concerned about the weather. Asking about what the weather is like is one of the ice-breaker questions in the English-speaking world. That is to say the change of weather affects our everyday life.

In terms of urgency, climate crisis is the greatest threat to mankind next to the covid pandemic. It brings chain reactions and shocks to multiple systems from water, energy, food to national security, finance and biodiversity. It once again tells us circular economy is the direction we should work hard toward by gradually decoupling growth from the consumption of finite resources. Yes, we’re already seeing many new types of jobs with new descriptions, including my recent epiphany to reframe a new hat for myself—Global Sustainability Writer. Precisely, I don’t just write about the environment but about the three pillars of sustainability—economy, society and the environment and the fourth—intergenerational equity.

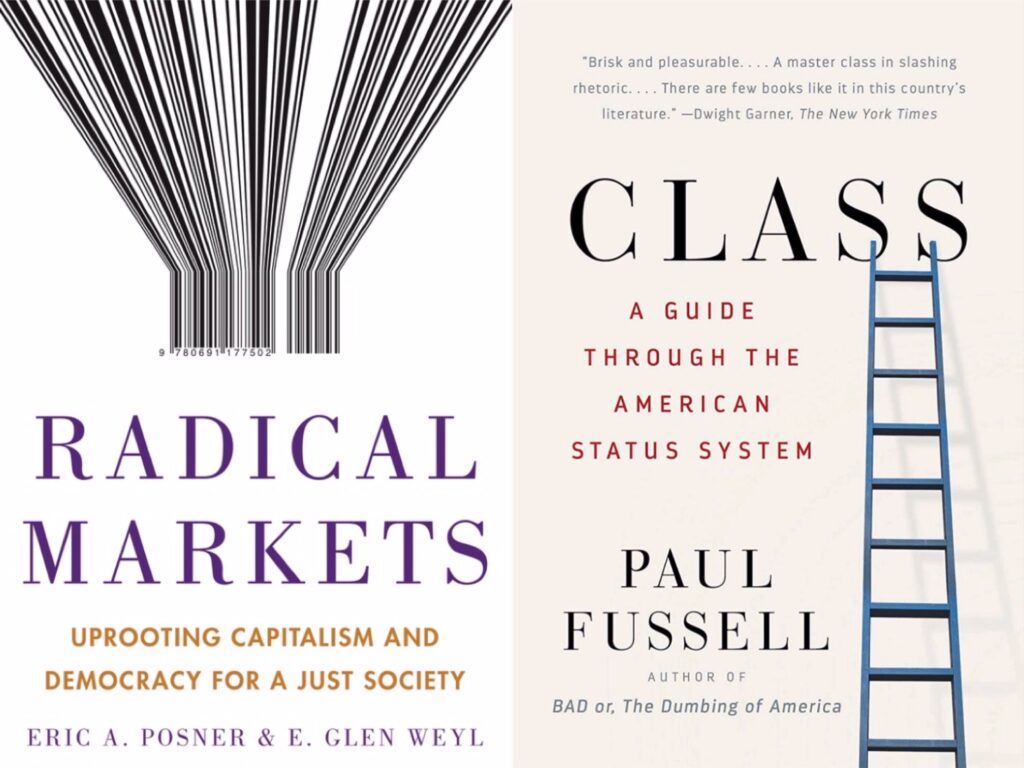

Evidently, the covid pandemic has caused an uptick of plastic use including disposable masks, gloves and single-use plastics in hospital supplies. This trend has no sign of abating. E-commerce shoppers are grown to enjoy the convenience of a house-bound economy. In the meantime, with the rapid development of e-banking and e-finance, the linear economic business practices are also facing challenges. The Internet has allowed consumers to interact with financial institutions directly through their computer and smartphone, forcing the spatial convenience to transition toward a digital one. Recently I’ve read two books—Radical Markets (2018) by Eric Posner and Glen Weyl and Class (1992) by Paul Fussell. Both of them are not an easy read and yet are thought-provoking for me to recognize the core problems in the U.S. and find solutions to address economic and social inequality.

In Radical Markets, the authors introduce the power of auctions based on Nobel Prize laureate in Economics William Vickrey’s ideas. They argue that “the rise in inequality and the fall in labor’s share are both fueled by and fuel a rich-get-richer dynamic.” The linear economy needs a long overdue “mechanism design” to solve major social problems that we are experiencing not only in the U.S. but around the world. Here, without reservation, I advocate for more “Solutions Journalists” to be added in various beats in journalism. To name a few, political reporting, food reporting, education reporting, health reporting, economic reporting, civic and law reporting and even photojournalism. A picture is worth a thousand words. A good storytelling image can evoke people’s to-do spirit and inform them with facts through visual techniques.

In solutions journalism, perhaps we should think about how we can create a narrative of solutions not only for the disadvantaged but also for citizens who feel the disruption will “downgrade” their status. Take the example of my plastic waste problem. Workers who make a living from producing plastic bags may feel a sense of accomplishment and dignity because they’re able to make a living from the fossil-fuel-dependent economy. But they will lose their jobs if, say, a solar farm replaces their factory. What if they read from credible news stories about how other peers successfully transform themselves by taking green jobs? What if solutions journalism provides resources for them to acquire employer-sponsored career training for these green jobs? What if they also find out from the media outlets that they can sign up for a technical training program near their rental homes? Our data-driven society is hungry for relatable stories like these.

If we understand the problem, we can create solutions to protect ourselves. I believe knowledge can be acquired. Skills can be developed. Abilities can be sharpened. Underprivileged people don’t have the equal opportunities to basic human rights including health, education, housing, water, sanitation and other services essential to their survival. Thus, in addition to government aid and NGO charities, solutions journalism will be their silver lining to make life-changing decisions. I hope information transparency allows every responsible citizen to not only release credible information for those who are in need, but also hold those distributors of fake news accountable. Perhaps solutions journalism will show us how to do fact checking with critical thinking. In my future posts I’ll share my discovery of sustainability solutions from a global perspective. I do request your support by spreading this free information for those who are in need. If you like my work (click here), partnership is what we can do better for what we care for.

By the way, the term “caste” in the U.S. wasn’t new. Sociologist Paul Fussell adopted it in his book Class nearly thirty years ago, long before the recent New York bestseller Caste (2020) by Isabel Wilkerson. As Fussell wrote in the opening chapter, class was a “touchy subject.” He added: “Especially in America, where the idea of class is notably embarrassing. In his book Inequality in an Age of Decline (1980), the sociologist Paul Blumberg goes so far as to call it ‘America’s forbidden thought.’” Now, forty years later we’re revisiting the same American wound against the backdrop of the covid pandemic, climate crisis and economic slowdown. Will solutions journalism show us the way to rebuild public trust for the societal institutions?