If my dictionary is correct, the speaker who owned this famous line: “Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink” was a sailor in English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s work, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The sailor was on a stranded vessel surrounded by salt water that he could not drink. Water is necessary for our survival. Access to clean water and sanitation is a human right. Among the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), SDG 6 is to ensure access to water and sanitation for all. Have many Americans, who access water directly from faucets and bottles without a second thought, thought of those who may be like that sailor as water scarcity becomes more critical?

In contrast with the fact that countries focus heavily on energy for development strategies, especially investment in clean energy, water is less regarded as a national security issue. As we are still living in a fossil fuel-based economy, we will consume more water to generate power in order to meet the growing energy demand. Even wastewater treatment plants need energy to pump water, and the energy in water can be used to produce electricity. Researchers found the U.S. energy system requires an estimated 58 trillion gallons of water withdrawals each year. Of that, 3.5 trillion gallons of freshwater is consumed. In other words, when we discuss energy, we need to factor in water. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to power.

Water is used by some water-rich countries as a political weapon. Or in China’s case, a political decision that few people dared to confront has diverted water from water-rich southern provinces to parched northern regions as part of a massive South-North water diversion project. The water diversion project has implications for regional ecosystems similar to those of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Using water as a political weapon is not a new idea but it has become more widespread as global water supplies are decreasing. Turkey takes advantage of hydropower as a political weapon against the Kurds. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers, two of the three longest rivers in the Middle East after the Nile, both originate in Turkey, making the country a hydropower state following the completion of a massive dam project last July. Now, climate change has aggravated drought condition in the region, drying up the ancient rivers. Turkey’s dams have significantly reduced water flow into the lowlands of Syria, where the Kurds are settled.

Syria’s political upheaval has a lot to do with water as well. Researchers found an extreme drought in Syria between 2006 and 2009 was most likely due to climate change. Where there is drought, there is a food crisis. Aridity in the Eastern Mediterranean caused crop failures that led to the migration of at least a million people from rural to urban areas. This added to social stresses that later turned into the shocking Syrian civil war against President Bashar al-Assad in March 2011. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to irrigate.

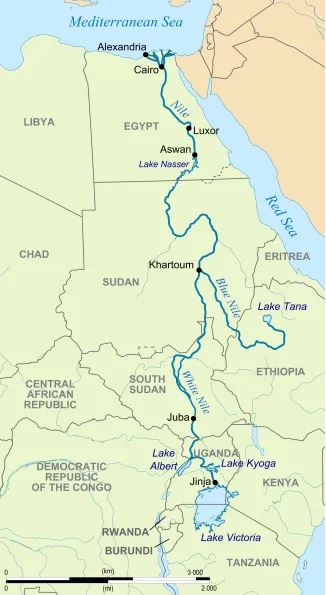

Many geopolitical conflicts are derived from water. From the Mekong River dams in Southeast Asia and China to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in Africa, conflicts over water access abound. Water scarcity becomes a threat to ordinary people’s livelihood as well as to the power of ruling parties or strongman leaders. Egypt has publicly denounced the hydroelectric GERD and its impact on access to the Nile’s waters as a major threat to the country’s water security. Thanks to Chinese banks, the Ethiopian government was able to raise money needed to start the construction of the GERD. More disputes about the GERD are expected to erupt in the region.

China is dealing with water conservation by exploring and adopting new technologies such as precision agriculture, drones, satellites, big data, machine learning, and automation in farming. Ocean crops have been a heated topic in the ag-food industry. If mankind finds solutions to the problem of growing crops in seawater, it might alleviate the agriculture sector’s dependence on freshwater, especially when its supply is threatened. In addition to a “Clean Plate” campaign against food waste, China accelerates rice cultivation in saline soil. According to Chinese state media, China has about 100 million hectares of saline-alkali soil, of which about one fifth could be ameliorated to arable soil. China’s salt-resistant crops will significantly increase food supply along the coast which used to be off-the-limit for agriculture. China is not alone. Such crops, also known as agrisea, are being introduced to several rice-producing and consuming countries such as Nigeria, Vietnam and Bangladesh.

The year of covid even makes the subject of water critical. Public health and hygiene are under threat in the Navajo Nation in America because the indigenous people have no water access to wash hands. If we care about well-being and sustainable development, we ought to place water first and foremost in long-term planning. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to reserve for future generations.