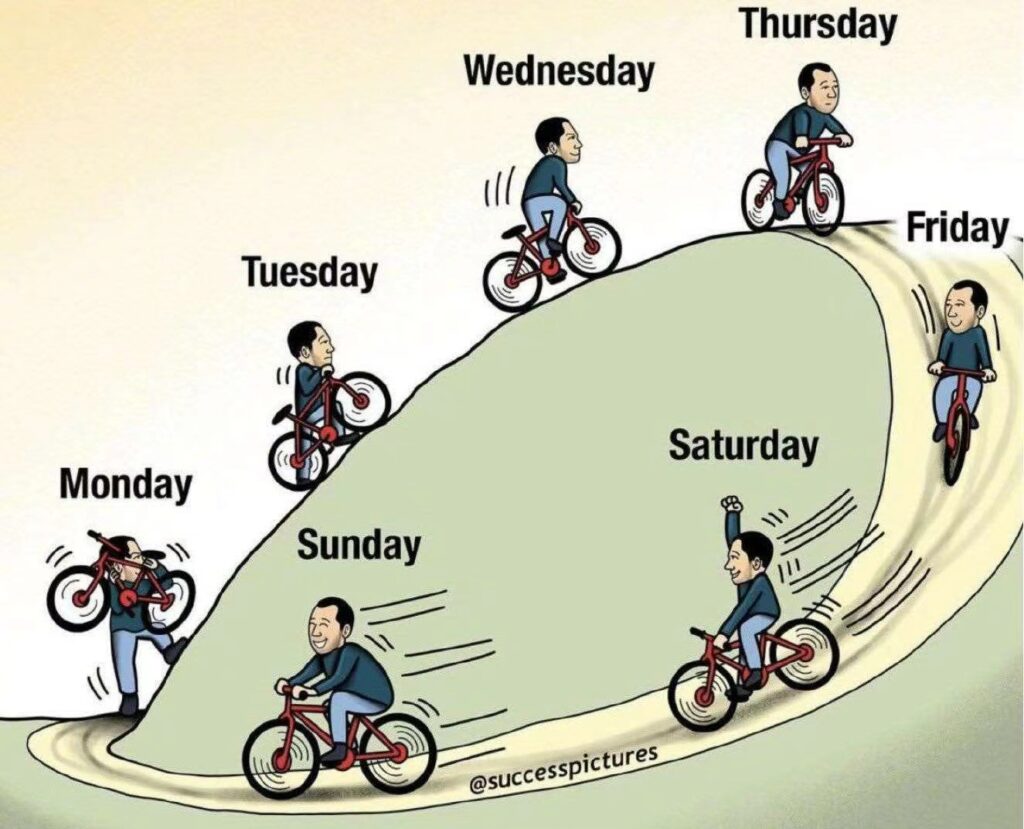

Imagine that when you refresh your smart phone the first thing in the morning, all you see in notification and story headlines are about laughing. What would be your first reaction? Has the world gone upside down turning to triviality? Or, has your world made the turn to accept all hard news with an ear-to-ear grin? I do look forward to that day when laughing becomes a law, a code of conduct, a foreign policy, and a necessity synonymous to breathing, food, water among others in the lowest level of Maslow’s pyramid of human needs.

When 2021 started a month ago, an array of new laws and regulations went into effect on January 1. In the U.S., covid-related laws included those offering help to essential workers, boosting unemployment benefits and requiring time off for sick employees. 2021 is the beginning of a new four-year presidency under President Joe Biden, signifying more legislative changes and compromises yet to come to fruition. In China, the country’s first Civil Code which was passed by the rubber-stamp parliament last May also took effect on January 1, 2021. Dubbed “an encyclopedia of social life” by many, the Code is composed of a total of 1,260 articles, covering a sweeping collection of existing laws and regulations as well as judicial interpretation related to civil activities and relations, such as property rights, contracts, personality rights, marriage and family, succession, and liability for tort. More recently, Chinese central government has released its first five-year plan (from 2020 to 2025) on building the rule of law in China. So from now on, there is central planning in a five-year interval for economic growth as well as in the judiciary arena in China. Will these official indicators make China Hands and pundits too busy to remember how to laugh at leisure?

Will the China’s version remind you of the Napoleonic Code (1804) which was established by French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte? If the Napoleonic Code is one man’s ideological architecture that watched over hundreds of thousands of presumably obedient commoners, China’s Civil Code solidifies the ruling party’s absolute power over the people and their private life. With the help of big data, the Code gives Chinese authorities amble reasons to collect, screen, manage and manipulate personal information. If there is measurable data, there will be manageable solutions to various social problems. If there is law, there will be compliance and resistance. China’s Civil Code will resolve some conflicts and trigger new controversies at the same time. It will substantially influence every citizen. If only lawmakers were to design the systematic compilation of laws for the best interest of the masses. However, securing power is the utmost purpose for a code, or the system of laws. James Madison once said, “Justice is the end of Government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be pursued, until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.”

A majority of people pay little attention to the changes of existing laws or arrival of new rules unless their needs and interests, both financially and psychologically, are impacted by them. I would not care about the Farm Bill unless the Farm Bill becomes a law and it will cause a spike of food prices, specifically, making my favorite zucchini more costly now than yesterday. China’s marriage rate hit eleven-year low in 2018, with the trend continuing at the start of 2019. The Civil Code requires a cooling-off period of 30 days before Chinese couples who want to dissolve their marriage can do so in an effort to lower the country’s soaring divorce rate. Heated discussion about the new law spread like a virus on the Chinese internet. Just glimpse at this statute about marriage and family, and you can see that I think the beneficiary is the society, or precisely, the party leadership, not the individual.

It is a pattern that the more economically developed a society becomes, the more stable the fertility rate is. The stable fertility rate in some developed countries and regions even declines. Europe, the U.S., South Korea, Japan and Australia have long been on the list of low fertility rates. Taiwan just joined the club of low fertility rate. The self-ruled island has its lowest fertility rate in 2018 of 1.06 children per woman, one of the lowest in the world. For the population in a given area to remain stable, an overall total fertility rate of 2.1 is needed.

China thrives on strong productivity and domestic consumption supported by a gigantic population base. But this system cannot be sustained without outer forces—as the country is steering toward a moderately prosperous society, or “xiǎo kāng shè huì” in pinyin, where the middle class dominates the majority of the population, China cannot escape the same pattern seen in other economically developed countries. One of the outer forces is the implementation of the Civil Code to influence citizens’ everyday activities from cradle to grave. The cooling-off period in the Civil Code may chill fiery domestic conflicts temporarily but engenders fear among young loving souls who might someday tie the knot.

If laughter is the best medicine, when I reflect on today’s Chinese society, I can only laugh at the Civil Code’s top-down approach to a man’s inalienable right to pursue happiness. I am a living proof of China’s notoriously famous One Child Policy which ended in 2015. In my memoir, I sympathized with Chinese women in my mother’s generation whose body and sense of self-efficacy were deprived of by the cruelty of this national policy. Every time I think of the draconian family planning policy, I think of education. When I traveled to Singapore years ago, I was told single women in that city state had “three highs”—high education, high pay, and high standard for Mr. Right. A sense of appreciation rose from the young me for those Singaporean women—with education, women know how to protect themselves; with education, contraceptive choices are made voluntary, not coercive; with education, women’s growth brings social progress, rather than threatening men’s constant socioeconomic insecurity in a patriarchal society. History would be rewritten had Chinese women received education about birth control instead of contempt and suppression from the society.

Robin Diangelo made a pithy remark in White Fragility that lingers on my mind. She wrote:

“While women could be prejudiced and discriminate against men in individual interactions, women as a group could not deny men their civil rights. But men as a group could and did deny women their civil rights. Men could do so because they controlled all the institutions. Therefore, the only way women could gain suffrage was for men to grant it to them; women could not grant suffrage to themselves. . . . white men granted suffrage to women, but only granted full access to white women. Women of color were denied full access until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

China’s high divorce rate did not happen overnight. In 2016, 50.6% of postgraduate students in China were female, exceeding the percentage of men for the first time. Women college graduates have outnumbered men in China. The same phenomenon has happened in the United States for roughly four decades but is not represented proportionally in the workforce yet. Compared to the old days with a rooted tradition of patriarchal societies, today’s Chinese single women in urban areas are more or less like the Singaporean women with “three highs.” While men continue to dwell on the fantasy of possessing power and dominance of women’s bodies for their want and desire, highly educated women in China are mocked as a sexless “third gender.” Will the Civil Code tame the third gender in China or unleash their civil wilderness?

Urbanites in Chinese big cities are no different from those in Singapore, Bangkok and Hong Kong, leading a middle class life with shelter, car and a secure job. A number of news stories have sounded the alarm that young people in Japan—particularly men—are turning their back on sex. “Sexless Japan” is now a reliable media meme bolstered by a plummeting birth rate and an aging population. If Chinese leadership cares about fertility rate and productivity, will they worry about Japan’s today becoming China’s tomorrow? Will the amended Civil Code expand to citizens’ love life in the future? Could the abolishment of Hukou system become reality in an amended legislation? That will definitely bring laughter to many separate families across China. In these broken families, children are left behind in villages with their grandparents while their parents are making money in big cities. Without an urban Hukou, rural children and their parents are technically second-class citizens in big cities.

If we know how to look for laughter as seen in our imaginary front-page news headlines, life is more than a seven-day cycle surrounding the familiar loops and turns. I’ve discovered two places to receive healthy doses of laughter medicine during this stressful time. The Laughing Ritual, or “Owarai-shinji (お笑い神事),” is held annually on the first Sunday of December in Higashi Osaka City, western Japan (in Japanese). Legend has it that the sun goddess Amaterasu secluded herself in a cave and the Gods laughed together to coax her out. They placed a Shinto rope, or “Shimenawa (注連縄 しめなわ),” on the cave to prevent Amaterasu from ever hiding herself away again. Last year’s ceremony at Hiraoka Shrine was an exception due to the pandemic. The priest and participants could not laugh out loud with their masks on. The other laughing activity originated from Mumbai, India in 1995 and spread around the world with a name called “Laughter Yoga.” Perhaps a little bit of laughter yoga will alleviate your stressful mind and vacate space in your heart to include a tad tranquility of life.

Laughing is contagious. When we can listen to other’s heartfelt laughter, we will then become part of it. When we learn to let go what troubles us the most, we will make room in our heart to accept the other, the unwanted, the uninvited, the unexpected, forming our own law of inclusion with peace. All in all, live laugh law.